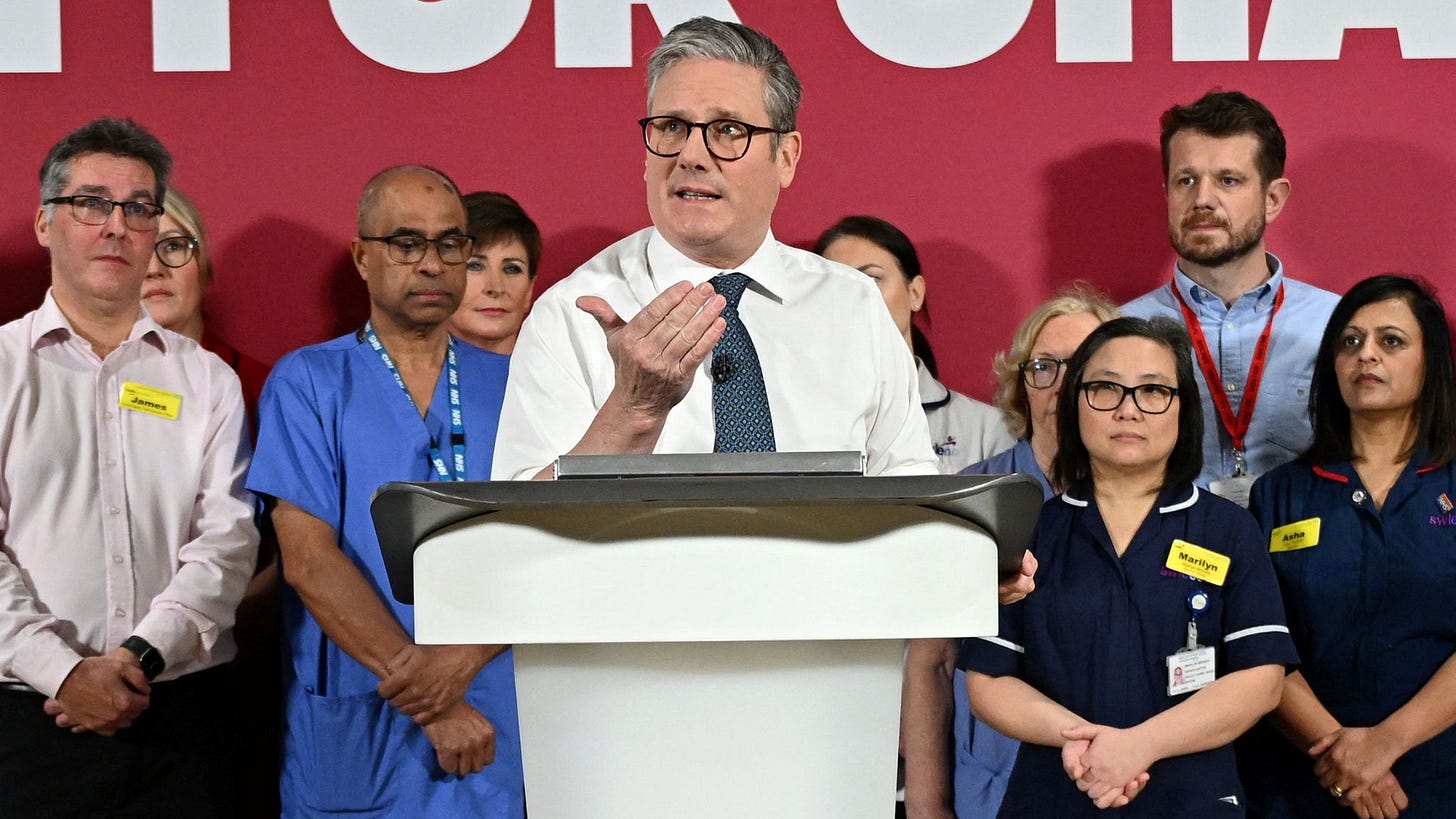

Starmer’s NHS reform is a step in the right direction, but there is still more to be done

(CREDIT: Reuters)

Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer outlined his planned changes to the NHS over multiple speeches across the previous week, packaged as an elective reform plan that he wishes to see implemented before the NHS receives anymore funding.

“I’m not prepared to see even more of your money spent on agency staff who cost £5,000 a shift, on appointment letters which arrive after the appointment, or on paying for people to be stuck in hospital just because they can’t get the care they need in the community.”

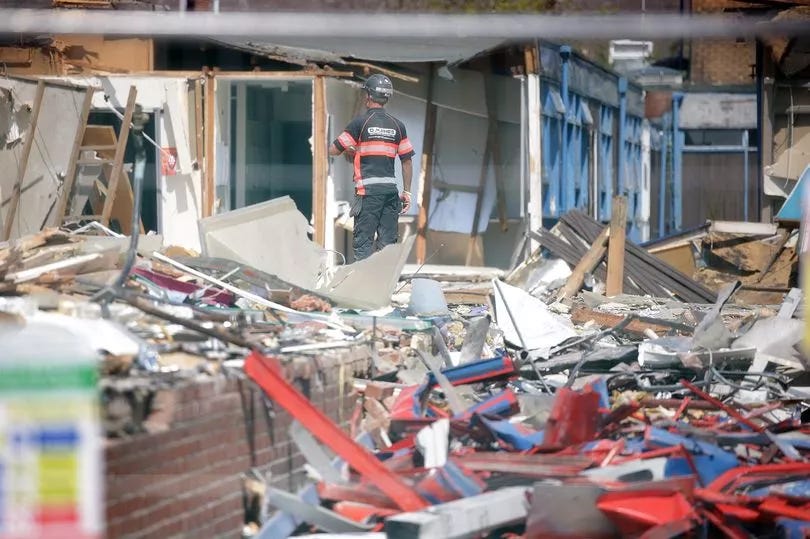

NHS reform has been something in the collective political consciousness for multiple years now. Ever since the freeze in budget increases made to the service made under the coalition government ¹, the service has become a shell of its former self, diminishing into an institution that is quite literally crumbling.

A photo of the outpatient ward at Stepping Hill Hospital (CREDIT: Manchester Evening News)

Starmer’s new list of reforms comes after October’s budget, which announced an ‘investment’ ² of £22.6 billion into the NHS over the next two years. Frustrations have been growing with the NHS with waiting lists now being measured in months instead of weeks, despite its reputation as the UK’s national religion. Starmer’s reforms are therefore put in place to streamline and to improve efficiency before the Service is trusted to receive a new injection of funds.

The headline target for the reforms is to reduce the average waiting time for an appointment to 18 weeks. How they seek to achieve this goes as following:

A new and improved NHS app: giving patients the opportunity to more easily track and follow appointments, aiming to decrease the amount of missed NHS appointments (currently 8 million every year).

Additionally, patients can receive test results in the app and be able to book tests/appointments from the app in a variety of locations, including Community Diagnostic Centres. This replaces the current system of receiving follow-up information by phone call or letter, which wastes time for the NHS.

- Labour are expanding the role of CDCs, having them open 12 hours a day, 7 days a week.

Furthermore, the NHS will use AI in administrative tasks to improve efficiency.

Giving patients more choice how they will receive a follow-up appointment, digitally, in-person, or not at all, rather than in-person appointments being automatically booked, which is aimed to reduce the total number of appointments on waiting lists.

The new app will also allow people to select what healthcare provider they will receive service from - including independent providers.

Health Secretary Wes Streeting, discussing the reforms, said:

“Our plan will reform the NHS, so patients are fully informed every step of the way through their care, they are given proper choice to go to a different provider for a shorter wait, and put in control of their own healthcare… This government’s reform agenda will take the NHS from a one size fits all, top down, ‘like it or lump it’ service, to a modern service that puts patients in the driving seat and treats them on time - delivering on our Plan for Change to drive a decade of national renewal.”

Given the scale of Labour’s targets (cutting average waiting times by over 80%), these reforms should definitely be met with some scrutiny. The reforms proposed are a step in the right direction, but are clearly not enough to achieve the lofty goals set out by Labour.

But then, it is true that these reforms are only the ‘starters’ to the real main course of the NHS reforms that Labour are serving up over the next year, billed as a ‘10 year plan’. The real meat and potatoes are coming in the spring, with more reforms in response to Lord Darzi’s independent report into the state of the Service ³, and the spending review, that will decide the funding framework for it in the coming years.

Given broadly what we have seen from Labour about the NHS so far - in the manifesto, from speeches, and from previous policy choices - it can be predicted that any future health reform will hit on the following points:

Refocusing NHS efforts toward community-focused care, away from hospitals - Labour hope that this can act as a preventative measure, and reduce the numbers of people that have to enter A&E and hospitals.

Doing anything to fix A&E, as the service is in a dire state. Long waits are estimated to cause 14,000 more deaths every year according to the Royal College of Emergency Medicine. Darzi’s report is mostly vague into what avenues could be taken to improve the Service however.

Increase capital investment - funds given to the NHS for investment (new instruments, new buildings) has been used to plug day to day gaps, leading to an NHS with decrepit infrastructure and machinery ⁴. Lord Darzi’s review finds a £37 billion shortfall of investment into the NHS compared to similar European countries.

Reform the management structure of the NHS. If you were to garner any point from Lord Darzi’s letter to the Health Secretary, it is that the NHS leadership structure is not well designed to lead an organisation as large as the NHS. Darzi explains the 2012 Health and Social Care Act ⁵ caused the Service to essentially implode from within, leading to an immensely inefficient and nonsensical system. The NHS constantly tries to reorganise itself, and the regulatory systems within the NHS are bloated and creates a system of internal governance that is often contradictory.

Again, there is nothing inherently wrong with these reforms. Most of these are important pain points within the NHS, and Labour would be right to address them. However, it fails to address arguably the biggest problem within the NHS - staffing.

There is an estimated staffing shortfall within the NHS of about 100,000. That shortfall handicaps the NHS in every operation it makes. Staff demoralisation has been well documented⁶ and is largely responsible for the current productivity issues within hospitals. Demoralisation has been found to be caused in large part due to stressful work schedules because of staff shortages. The holes in staffing were further exacerbated during the Coronavirus pandemic, with a 2021 independent review finding 92% of NHS Trusts suffering from some form of large-scale burnout, mental health, or stress problems. The King’s Fund states that these staff shortages “worsens wellbeing, increases the rate of sickness absence [by 18%], and exacerbates the problems of staff retention within the NHS”.

These issues make the NHS an increasingly less attractive place to work for young aspiring medical professionals. These BMJ found that one in three young medical students plans to leave the NHS within two years of their graduation to either work in the private sector or abroad. Already amongst the NHS workforce, a third of doctors say that they are considering leaving the country altogether according to a survey conducted by the BMA. The NHS can simply not afford a workplace crisis like the one it is currently having. The UK already has far fewer physicians relative to population⁷ than our developed European counterparts, and a workforce migration away from the NHS could very easily render the service unfixable, no matter how much money is thrown at it.

It could be argued that Labour has already made a start on this, with the Government announcing a ‘refreshed’ workforce plan (replacing the current June 2023 plan) to be released in the summer. However, all of the problems laid out by Streeting in the pre-release do not address the systemic cause of under-recruitment within the NHS: the complete lack of medical students.

https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/Epgix/1/

The UK has one of the lowest rates of medical graduates compared to population relative to other similar countries, and is much lower than the EU average of 17.5. This statistic becomes increasingly more nonsensical when you consider the number of quality medical schools the UK possesses - having 4 of the top 10 schools worldwide, and 27 of the top 250. The UK medical schools have the capacity to be training some of the highest quantities of professionals in the world, but they aren’t. The answer to why this is is simple: the cap on medical students.

Currently, the UK places a hard cap on the number of people accepted into medical schools, at around 9,500. Labour have previously promised to expand the number of medical students to 15000, but that pledge was mysteriously absent from their 2024 manifesto. The Medical Schools Council calculate that raising the number of medical students accepted annually by 5,000 would have a ‘public cost’ of around £1 billion. To increase our medical students levels to be the highest amongst OECD countries therefore, the yearly cost to the tax payer would be around £2.5 billion (including expenses for other potential issues, like hiring new professors 8). Considering the October budget already appropriated £22.6 billion for the NHS over the next two years, this is a very achievable policy for Labour to implement 9. It should not controversial to increase the proportion of graduates trained in medicine and healthcare. Furthermore, if Labour want to double down on this commitment, they could continue the Conservative policy of opening more apprenticeship medical courses to help address the staffing issues at the lower levels of care, and introduce measures to make the work-life balance for NHS professionals less toxic (more community care focus is a good start on this) to attract those coming out of medical schools to the NHS.

To conclude, Labour’s reforms are promising for the NHS, but they still fail to address one of the main root causes within the NHS - staffing. Labour’s 10 Year plan for the NHS needs to prioritise expanding investment in training and retaining the medical workforce.

¹ Labour had previously grown the NHS budget at an average rate of 5% every year, this reduced to around 1% under the Conservatives. See BMJ’s look into the history of NHS spending, 2023;380:p564.

² I say ‘investment’ in quotes as it is likely that a large amount of the increase of spending will not fall under the category of capital investment, instead being used for day to day spending. The House of Lords Library states that on average, 2/3 of the spending from the budget will be day to day spending.

³ The report wasn’t exactly ground-breaking, but is broadly helpful for predicting what Labour’s future NHS reforms may look like - with it broadly focusing on the lack of community care, and lack of capital investment. The report is an interesting read - if you want to read the summary, click here.

⁴ This is despite repeated attempts by the Conservative government to allocate funding for machinery for the NHS. The lack of capital investment can be seen most clearly in the current state of NHS hospitals, like the case of an unnamed hospital that is currently unable to treat obese patients on upper floors due to the risk of the floor collapsing.

⁵ The Act essentially abolished the NHS leadership structure without any replacement. Furthermore, it cost the service tens of billions in pointless reorganisation costs and contributed to the NHS staffing shortfall.

⁶ Darzi’s briefly touched on this in his report, but this press release by the Royal College of Nursing I found to be a far more comprehensive look into the effects of the crisis of demoralisation in the NHS, painting a picture of a death-spiral where staff leave after being demoralised - by other staff leaving.

⁷ The UK currently employs 281 physicians per 100,000 people, relative to 388, 320, 400, and 451 in Spain, France, Italy, and Germany respectively. All data via the European Commission and Statista.

8 A Research Briefing given to parliament outlined a number of issues with raising the cap - such as the number of staff capable of teaching medicine. However, it can be assumed that there is likely enough people who have interest in becoming a university professor, that this problem is one that can be sidestepped.

9 It can be argued that increasing the cap on university students would simply lead to ‘worse doctors’. This assessment is plainly wrong, given the extent to which medical places are sought after. Take for example Kent University, which currently offers a Medicine program, and it considered to be one of the least prestigious medical schools in the UK. It has a 3 in 20 acceptance rate, with the average applicant having 3 A’s at A-Level. Meanwhile, the most prestigous University course in the UK, Oxford PPE (Sunak, Cameron, May, Johnson, Blair, Heath, Wilson all studied it), is more likely to accept applicants, at a rate of 1 in 5 (33% more than Kent medicine). All data is from UCAS.