Punish Productivity, Reward Ownership

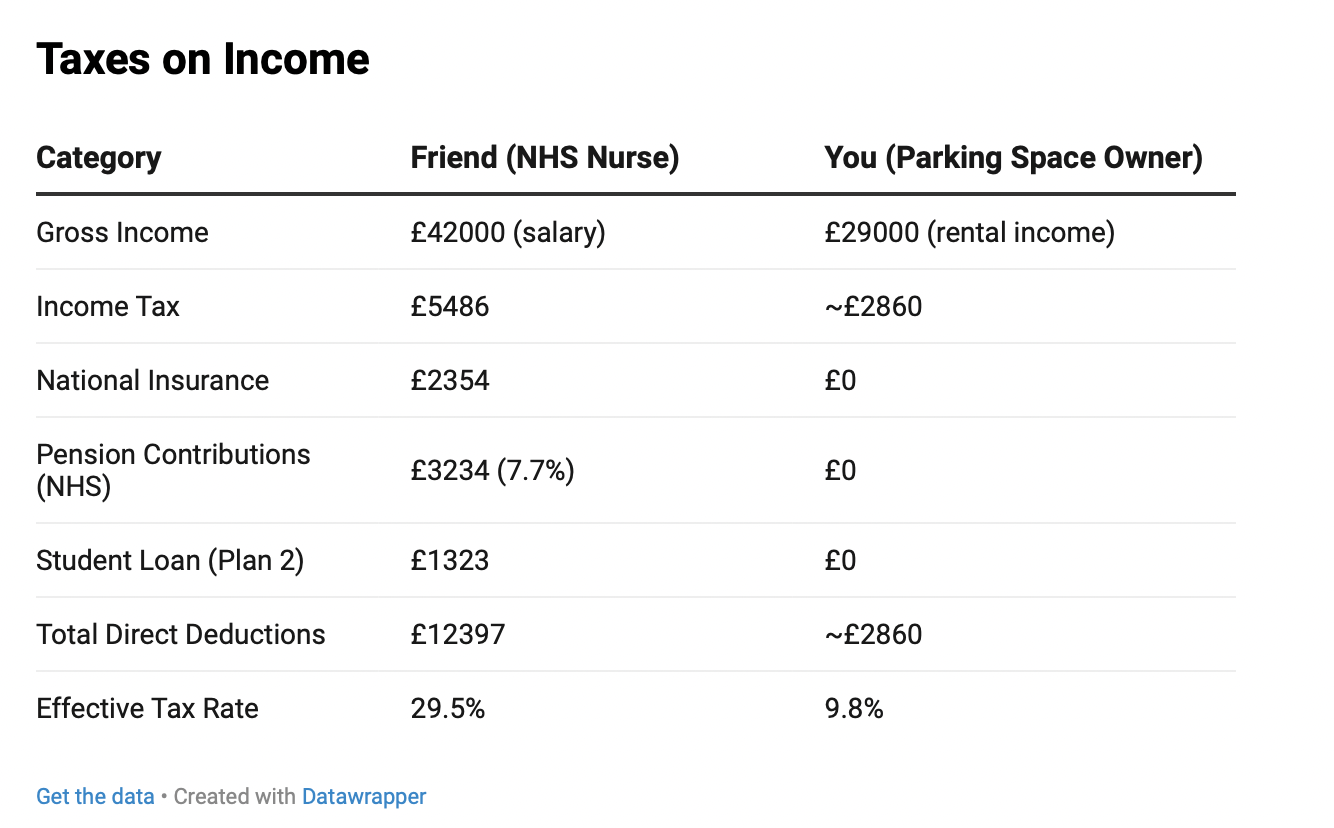

You have a friend, who works a nurse. She has a degree in nursing and a postgraduate diploma in advanced clinical practice. She is employed at St. Thomas’ Hospital, where she works night shifts, and is regularly exposed to trauma from patients.

She receives £42,000 in salary. She is then subject to pay £5,486 of that in income taxes. Another £2,354 is paid in National Insurance contributions. Being auto enrolled in the NHS’ pension scheme, she pays in an additional £3,234. It is then time to pay student loans for her costly degrees - taking out an additional £1,323. That amounts to £12,397 in contributions, or an effective rate of 29.5% on gross income.

Thankfully, your car parking space is worth around £300,000. You decide to rent it out for each day which adds up to around £29,000 a year. You pay £2,860 in income tax. That is the only tax you face, meaning you face an effective rate of 9.8% in tax.

In the end, she will only take away £29,603 a year, while you take home £26,410. Not bad for just renting out a singular parking space! After you finish your hard day of work, your friend tells you about her particularly rotten day at the hospital.

There is an obvious injustice here, that being how the tax system has rewarded your complete lack of economic contribution. However, this is no mistake. This is the British social contract working absolutely as intended.

The Rentier State

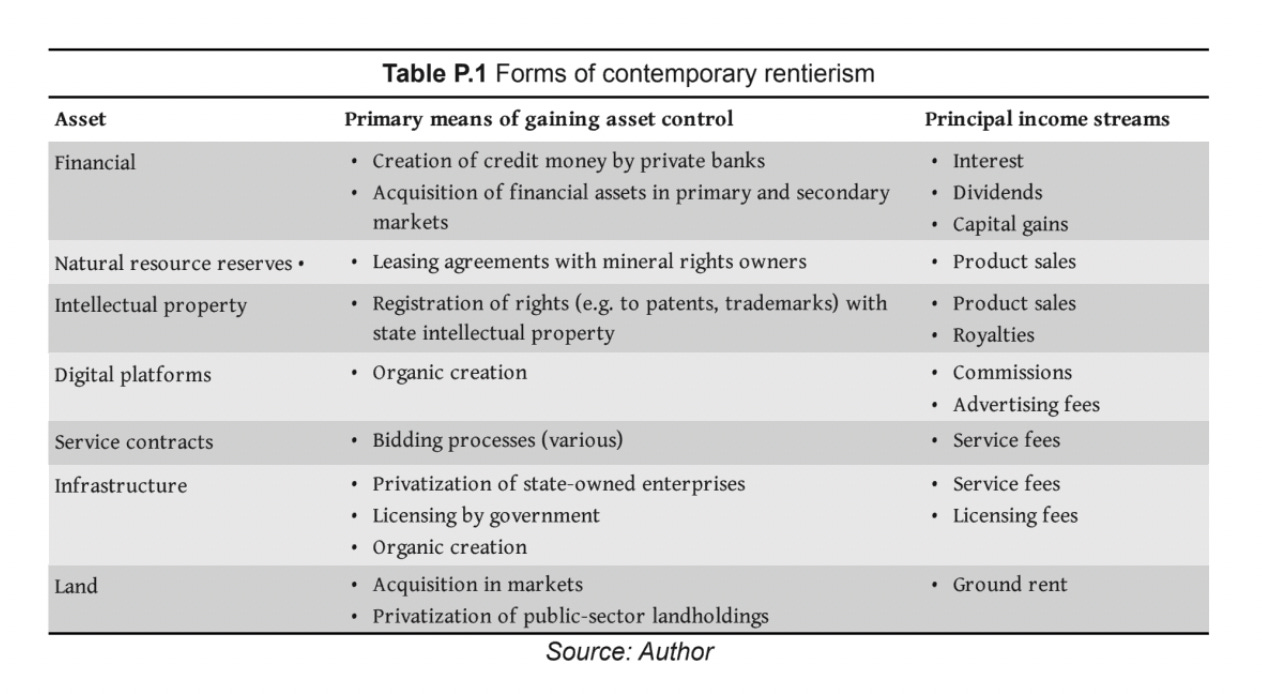

The above example may be a tad extreme, however it still does not dismiss the overall point, that being the UK economy and society overwhelmingly punishes the utility provided by work against the lack of such provided by economic rent. When I refer to economic rent here, I do not mean to just refer to its typical association with just property, but to its holistic definition as income gained not through the provision of utility but instead gained through simply the ownership of a scarce resource - that includes rent; but could also be Intellectual Property, or infrastructure.

This systemic imbalance between productive labour income and the unearned surplus of economic rent has made Britain into a rentier state. In the rentier state, the wealth does not go to those who contribute to the economy, but instead those who own the economy. The state is complicit, reinforcing this system as seen above with asset-generous tax policy. This article will seek to understand how this economic order came to be; what effects it really has on the economy; and finally - what policy we could implement to address it.

The Origins of Rentierism

The Towns and Country Planning Act of 1947

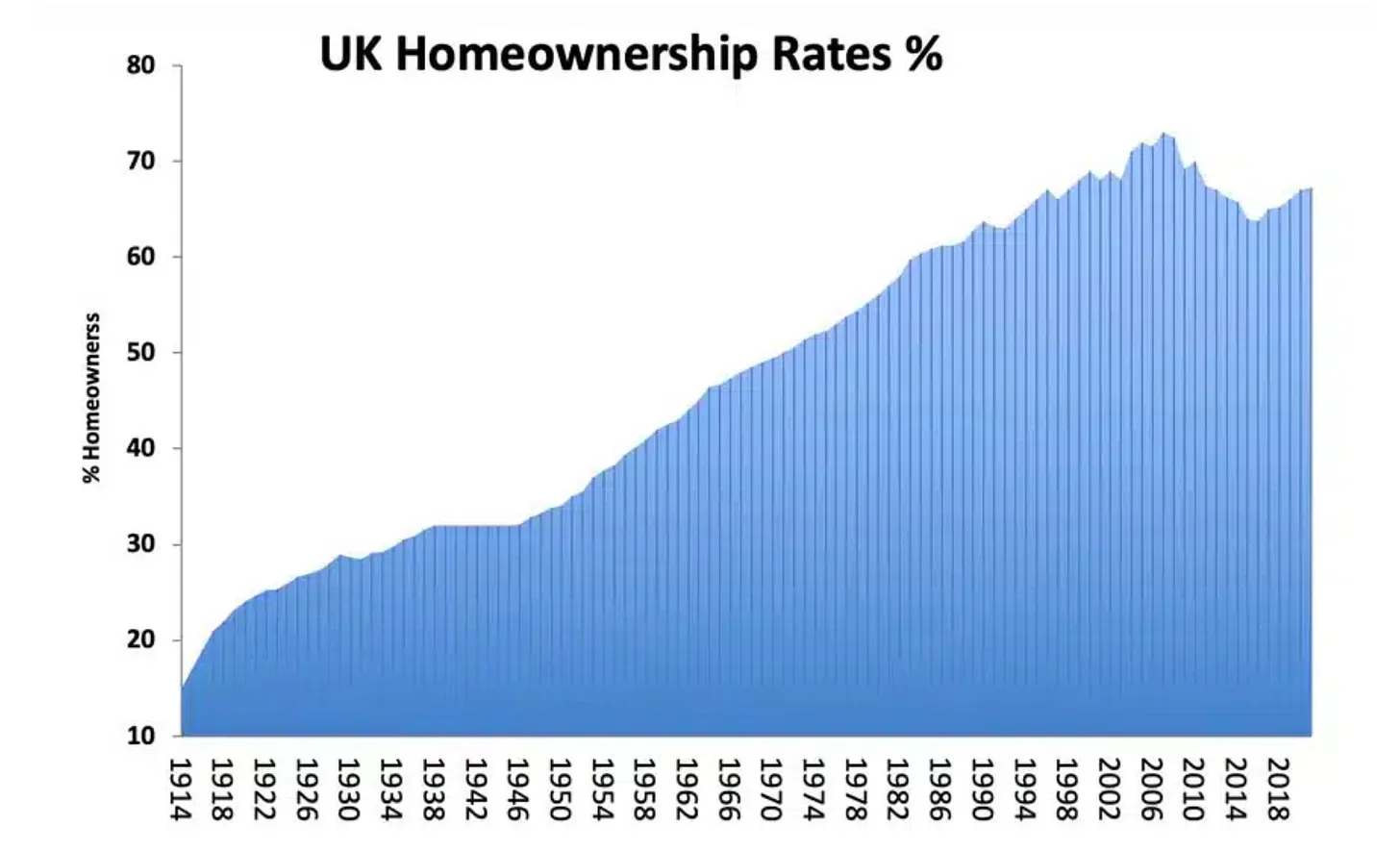

During the post WW1 period, Britain experienced a housing boom. British governments introduced subsidies for construction of housing in the 1919 and 1924 housing acts, and the cheap money policy (with interest rates being around 2% at points) allowed for a strong incentives for private developers. Furthermore, public sector development was also beginning to pick up around this point, with restrictions on building being incredibly lax around this point, with councils being able to contribute around 60,000 a year during this point.

A lot of building during this point was focused on urban ‘slum clearance’, with families in lower class areas being relocated to new public housing in the same area. Public transportation was being upgraded, allowing for a more rapid growth of suburban areas that had not been possible before. Housing construction nearly doubled from 1932 to 1934, going from 142,000 to 286,000, with these high rates of housing construction being continued until the Second World War 1. The semi-detached homes built during this period are now the quintessential image of British suburbia.

1930s Semi Detached Homes. Source: Urban Architecture

This supply side expansion had a large positive effect on the economy, as described by Professor Nicholas Crafts in the Guardian, “In every year from 1933 to 1936, before rearmament could have made any difference, growth exceeded 4% per year. Growth was not driven by fiscal stimulus; indeed it blossomed at a time of fiscal consolidation.”

The balance during this time period during the productive labour force and asset owners was far more prescient an issue. The DLG-era debates on what role the British nobility should play in society were still within recent memory, and British society was still breaking out of its rigid class system that had defined it for centuries. The asset-owning class was even more exclusive, but its accessibility was growing quickly. People were more willing to accept development due to the compete lack of housing stock across the country. Even the now revered ‘greenfield’ sites were not safe - a Manchester development carpeting thousands of acres of farmland with 8000 new units of housing can be used to exemplify this much different attitude.

Rates of homeownership exploded after the end of WW2 due to increases in housing stock seen a decade prior. Source: Tejvan Pettinger for Economics Help

As Watling describes - “This housebuilding was, in part, a victim of its own success”. The rapid urban sprawl had spawned a backlash against the housebuilding.

The Council for the Protection of Rural England (CPRE) emerged from this backlash, combing urban planners and supporters of Ebenezer Howard’s ‘new towns’ movement, lobbying for new restrictions on homebuilding to reshape the nature of housebuilding. Sir Abercrombie was appointed to lead the Barlow Report on housing.

His conclusions revolved around a belief that growth in London and Birmingham had reached their limits, and were beginning to cause an unsustainable level of sprawl. He argued for a new restrictive strategy that would allow for developers to look north.

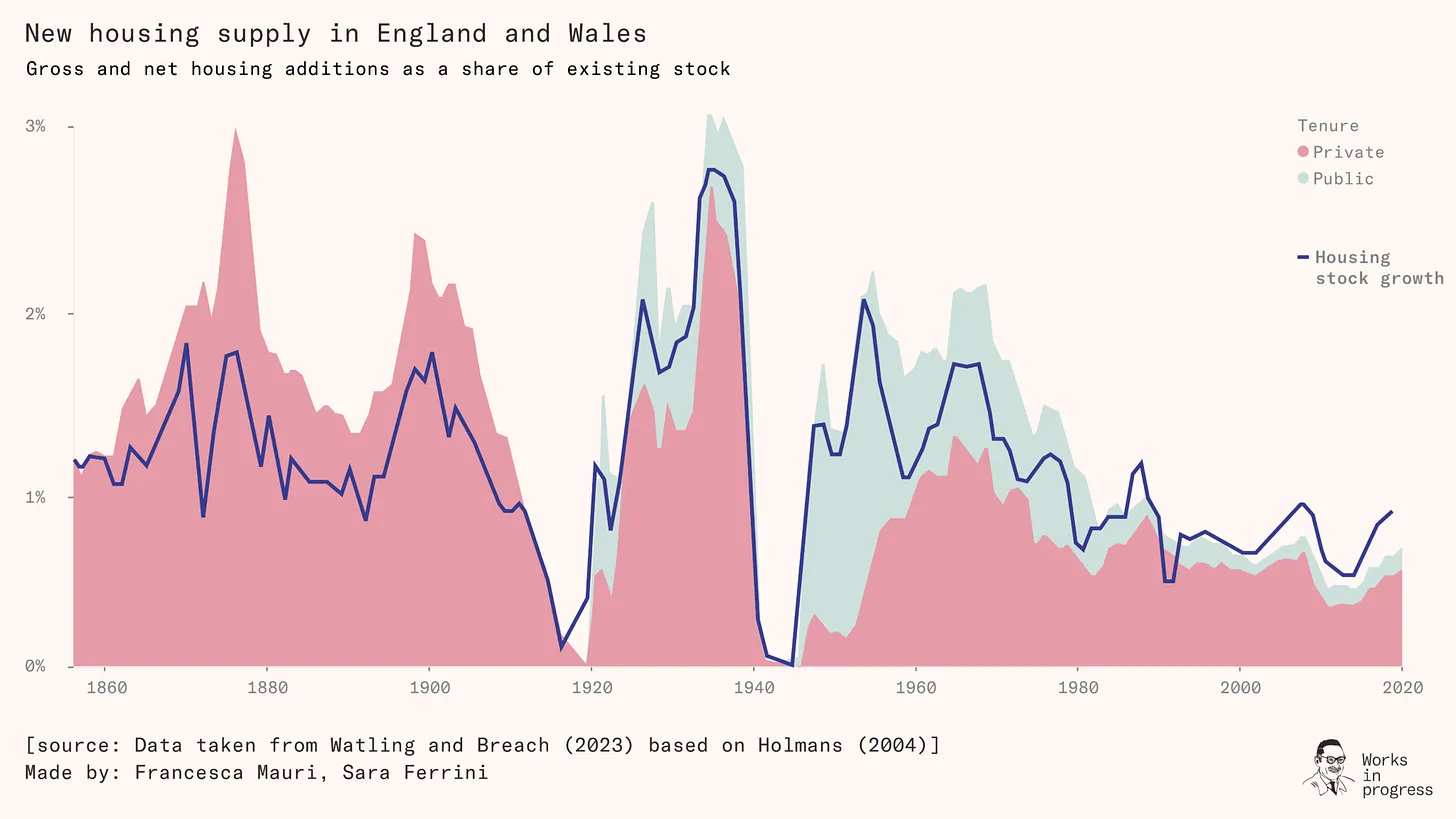

The newly elected Labour government combined the recommendations of the Barlow report and their own desire for state-built housing into the Towns and Country Planning Act, passed in 1947. The acts main provisions were to ensure housebuilding was in the public interest. Placing large restrictions on private construction, essentially being banned without explicit permission, was justified by the introduction of huge new council homebuilding programs that proponents argued could keep levels of homebuilding high while minimising the negative external effects of urban sprawl.

Social housing supply increases were enough to match the massive negative impacts on the private sector. Source: Samuel Watling in Works in Progress

The introduction of the Planning Act is a prime example of how rentierism can creep into the economy. It’s negative effects were offset by very strong social sector housing growth, but it set the stage for a market for housing that, as rates of homeownership increased, would become controlled by a new dominant asset-owning class who have incentives to ensure housing isn’t built at all costs.

It is important to acknowledge that the act did make sense given the context of the times. Urban sprawl was threatening some aspects of UK society - and construction of ‘new towns’ was successful during this period thanks to strong central planning. Supply for land was elastic enough to ensure that development was still possible. But as council bureaucracy ramped up, the supply for land became more and more distorted, creating a scarce supply of land controlled by asset-owners 2.

The Post War Consensus

Despite the distortive effects of the TCPA, levels of social mobility in Britain during the post war period were beginning to rise. Huge levels of social housing construction was enough to offset lost private stock, and a series of other reforms made under successive governments were also enough to continue the positive trajectory of mobility within the UK.

The Education Act of 1944, more commonly known as the ‘Butler Act’, named after its strongest proponent, R. A. Butler, had a profound impact upon British social mobility. Education was made compulsory until 15 and state schools were liberalised, increasing levels of education across the country. Powers over education were devolved to councils under the system. The impact of the legislation was immense, and today, free education is now taken as a birthright. The Robbins Report of the 1960s continued on expanding education, expanding access to university.

Expansions of infrastructure, both public and private, enhanced geographical and hence occupational mobility. The establishment of the British deity, otherwise known as the National Health Service in 1948 was another landmark achievement. Allowing for the productive worker to avoid impoverishing health traps, free at the point of access.

These pieces of legislation allowed for a great enhancement in social mobility as seen below; with levels of mobility (measured by net changes in long run occupation) increasing over this period of time and peaking during the 1970s.

It is important to note that these reforms were not exclusive to Labour, the Conservatives, or the Liberal Party. These reforms were accepted by most sides of the political spectrum, hence the name ‘post war consensus’.

Despite the state led language of these pieces of legislation, the private sector of Britain was also thriving during this time period. The Industrial and Commercial Finance Corporation (ICFC) of the BoE had some 2000 Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in its portfolio. SMEs accounted for 40% of product innovations in manufacturing, and employed over 30% of the manufacturing workforce. Decentralised SMEs were a strong tool for decentralising power across the UK away from London, with the 1945 Distribution of Industry Act pushing investment into areas such as Yorkshire and the Midlands. The decentralisation of power that SMEs bring was crucial to ensuring a balance between rentier and worker rights during this period.

A key element of the rentier-worker relationship during this period was the Schedule A income tax. The tax was on the benefit/income derived from the ownership of property. For example, for the case of our car parking space owner above, it meant that the current rate of tax of around 10% would be around 35% under Schedule A rules.

Thatcherism

Contrary to the belief of many on my side of the political spectrum, the post-1979 reforms of Thatcher is in fact not actually the root of all evil within the UK.

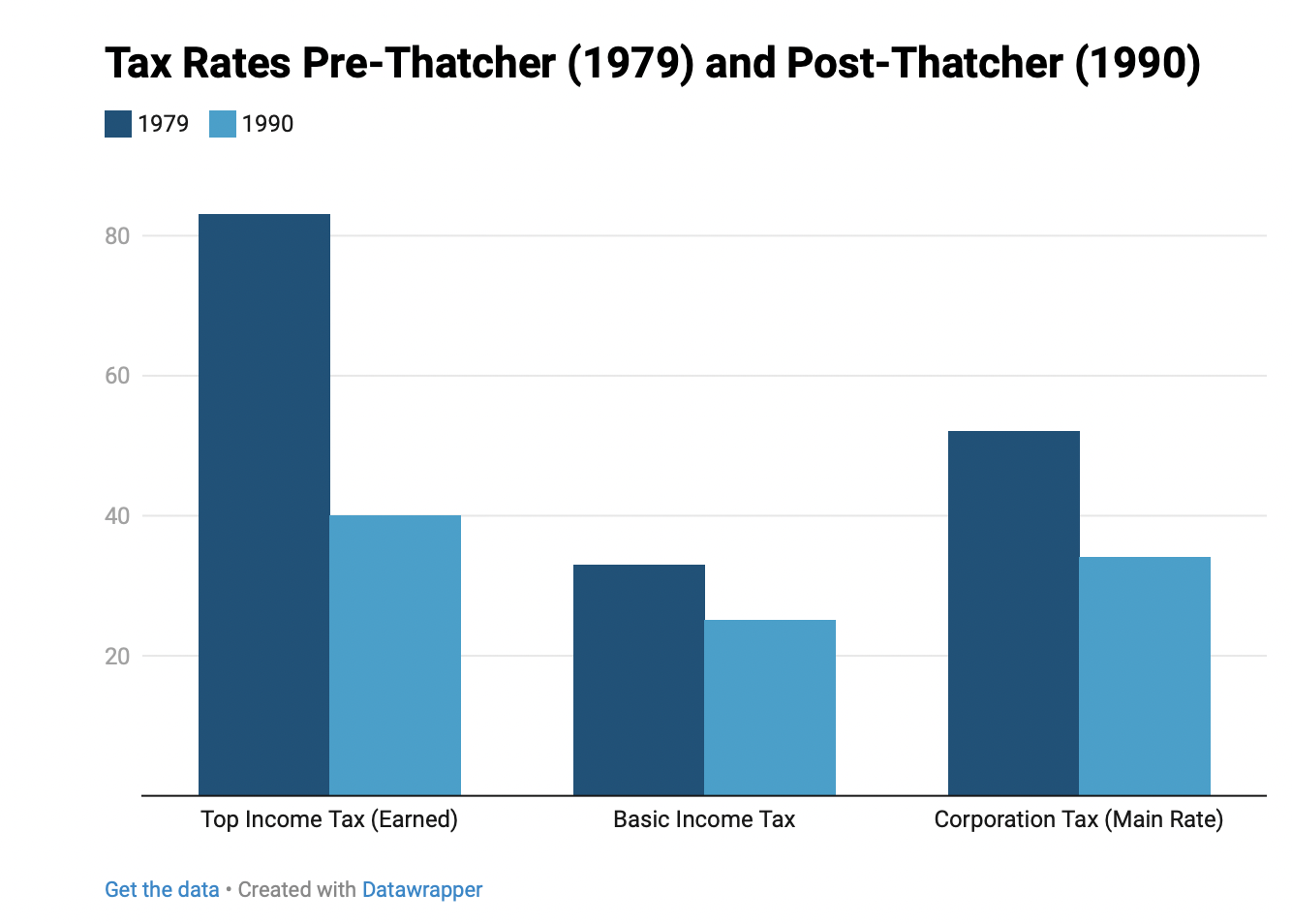

One side of the post war consensus that I failed to mention was the extraordinary high rates of taxes that were levied upon productive elements of the economy to fund the welfare state. The Thatcherite prerogative was to end these levels of taxation.

The rejection of post-war dirigisme had noble intentions, aiming to restore private sector productivity and individual iniative to the economy. The tax cuts for productive enterprise and labour were aimed to do so.

However, these cuts were a doubled edged sword. As shown above, rates of asset taxation upon rentiers were also slashed. These reductions ultimately tipped the scale towards asset owners. Capital gains exemptions in tandem with the financial ‘big bang’ 3 allowed for positive growth in UK financial services, but the tip in power towards asset owners ultimately meant such appreciation came at the cost of the prosperity of the productive sector of the economy.

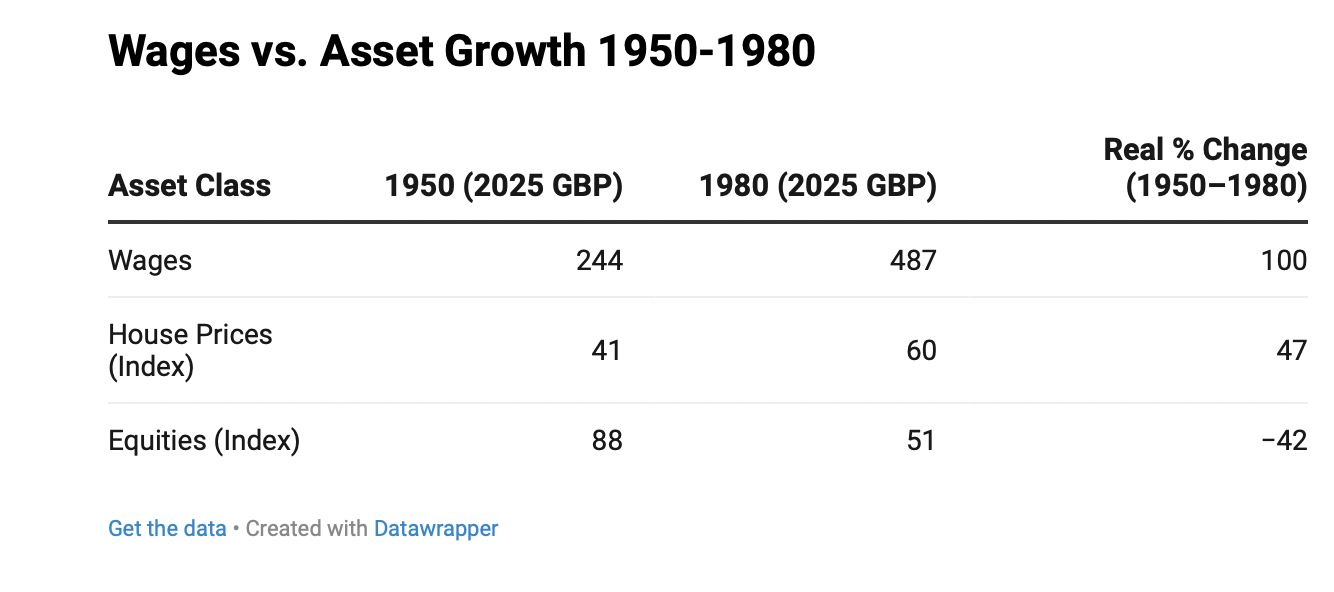

For reference, these were the increases in wages vs. various asset classes from 1950 to 1980 (the post war consensus era)4.

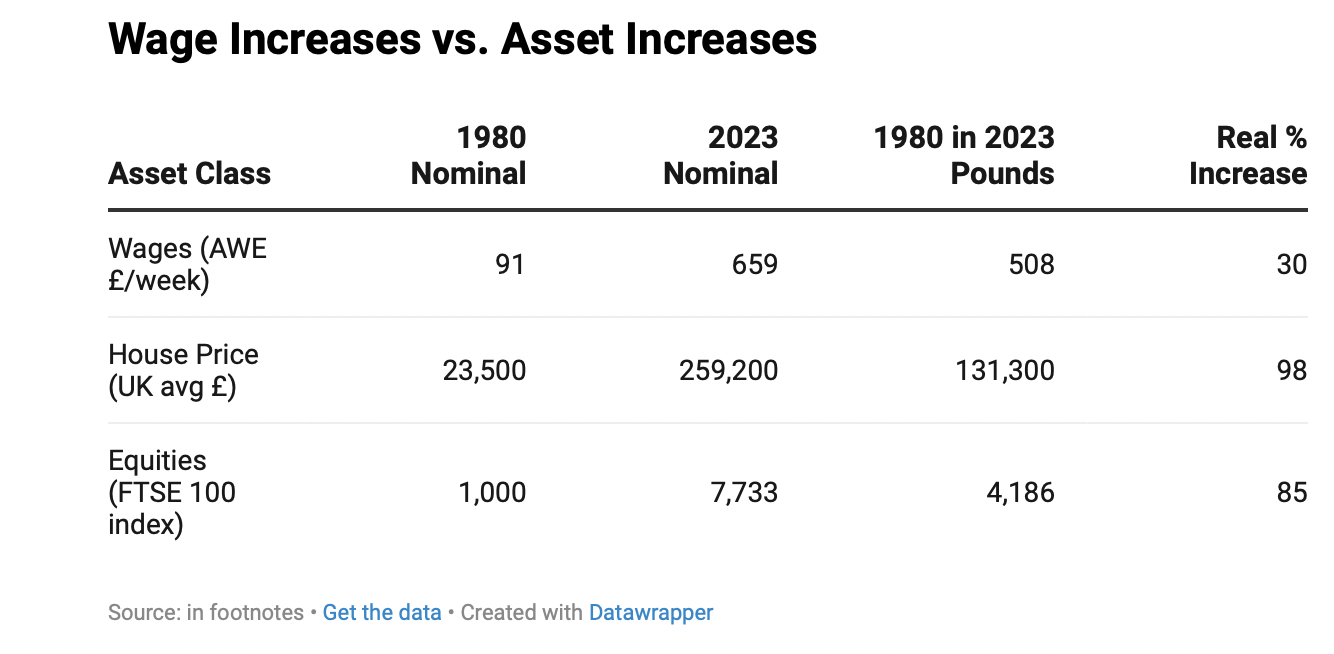

Now compare that to the data from 1980 to today 5.

Thanks to the TCPA discussed earlier, housing grew significantly during both time periods, at least to other asset classes. However, after the reforms, we not only see an a sizeable increase in the rise of house prices, but also a notable increase in the rate of other asset classes, with equities being the example in the data. Furthermore, wage growth started to slow.

In an attempt to incentivise homeownership, the 1963 Budget under Reginald Maulding abolished Schedule A Income Tax. This was mostly in line with the expansion of the property owning class that had occurred thanks to the housing booms of the 30s. The reforms had the unintended consequence of rewarding asset hoarders, meaning that the unearned income of rentiers were no longer subject to the same level of tax.

The tax was effective at punishing asset hoarding as established earlier in the essay - but Schedule A also served as a crucial incentive to utilise property, with the policy potentially having an impact on vacancy rates 6. Its removal made the opportunity for asset owners negligee relative to gains. Reforms under Thatcher like the indexation of Capital Gains further helped to reinforce the rentier economy.

The Entrenchment of Rentierism

The Thatcher era reforms enabled a growth in the rentier state, and the New Labour continuation allowed them to fester. The impact of the policy can be seen in the growth of rentier assets, with property rent and IP rent both experiencing large appreciations.

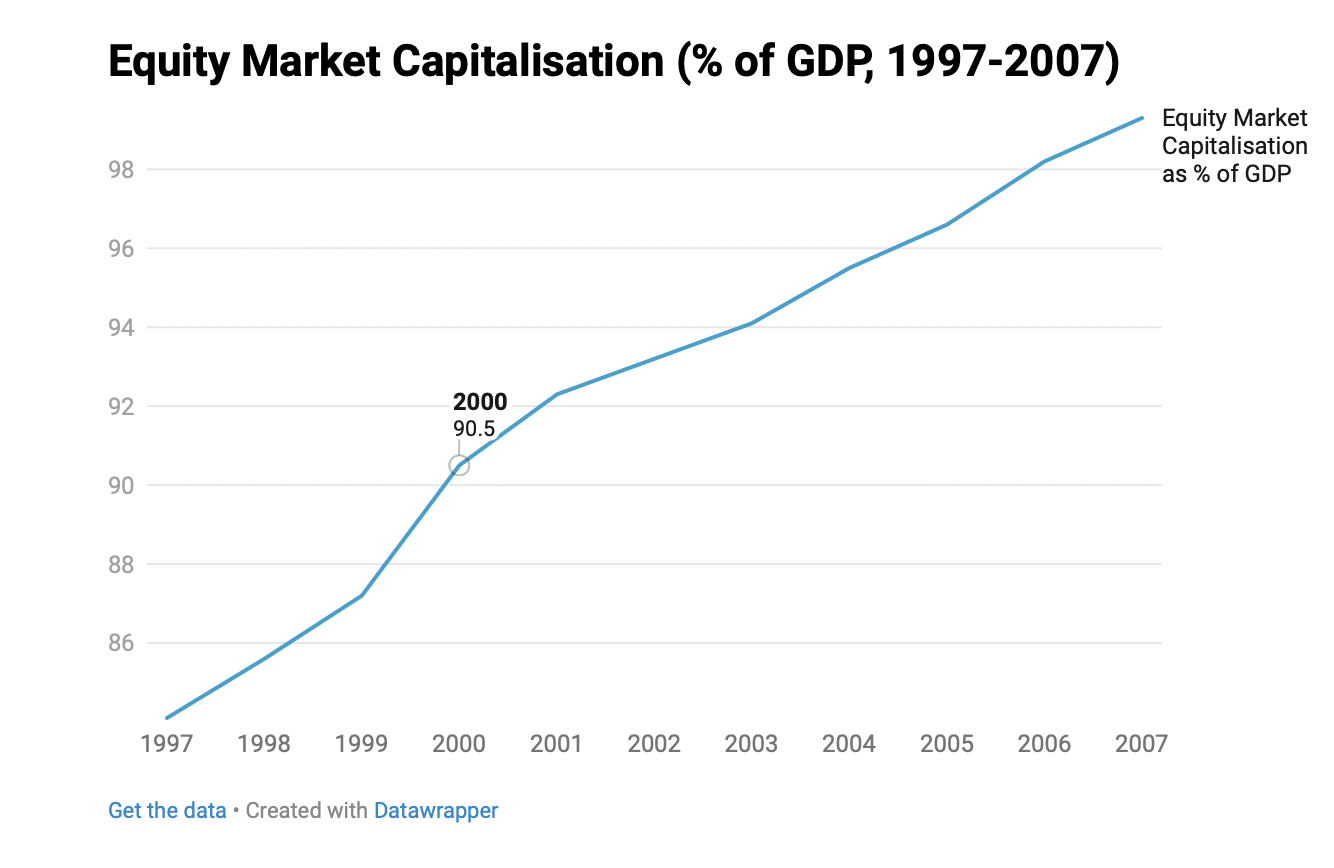

The New Labour era delivered impressive economic growth and societal welfare. Investment in public services grew, and unemployment was falling. The embrace of globalisation allowed for the late 90s to early 2000s to be a period of prosperity in Britain. As shown above however, underlying the growth was a decoupling between growth from the rentier economy and the productive economy.

Some of this growth was hence neither inclusive or sustainable, as large sectors of the economy began to become centred round asset bubbles.

Financialisation was both a cause and symptom of the rentier economy. Financial markets increasingly became a tool of the rentier sector to maximise short term asset returns. This can be demonstrated through the growth of Equity Markets.

The Great Financial Crisis

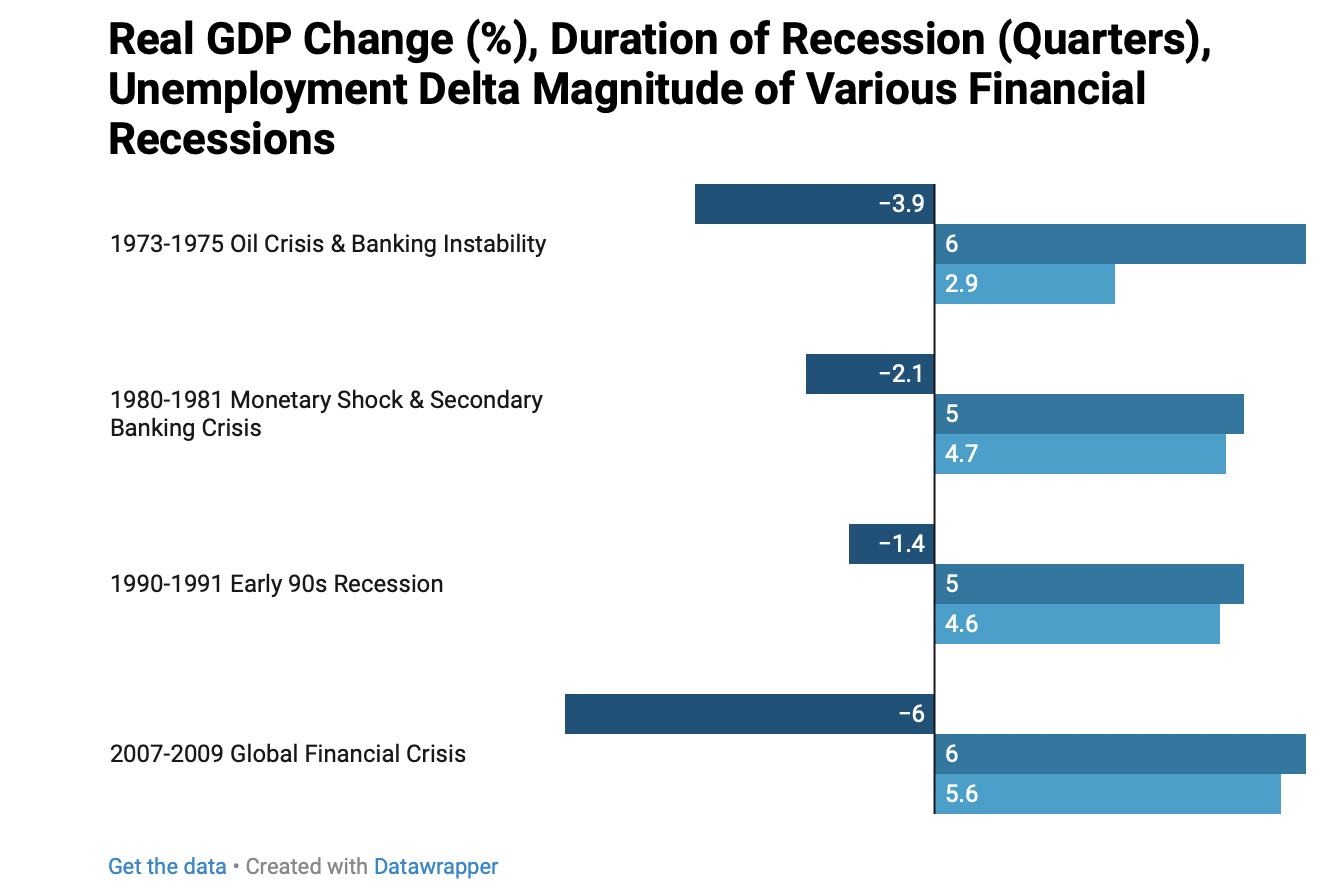

We have already established how the post-Thatcher rentier consensus caused the economy to become centralised on a semi-exclusive group of assetowners. The rentier financial institutions unsustainability was shown by the scale of the collapse during the GFC.

The financialisation of the economy meant that when financial institutions suffered as a result of the collapse of subprime mortgages, the whole economy suffered as a result. Much more so than in previous financially-incited economic meltdowns.

Note: Delta (Δ) for the purposes of tables/charts in this article refers to its mathematical definition; that being the change in the magnitude (quantity) of a statistic)

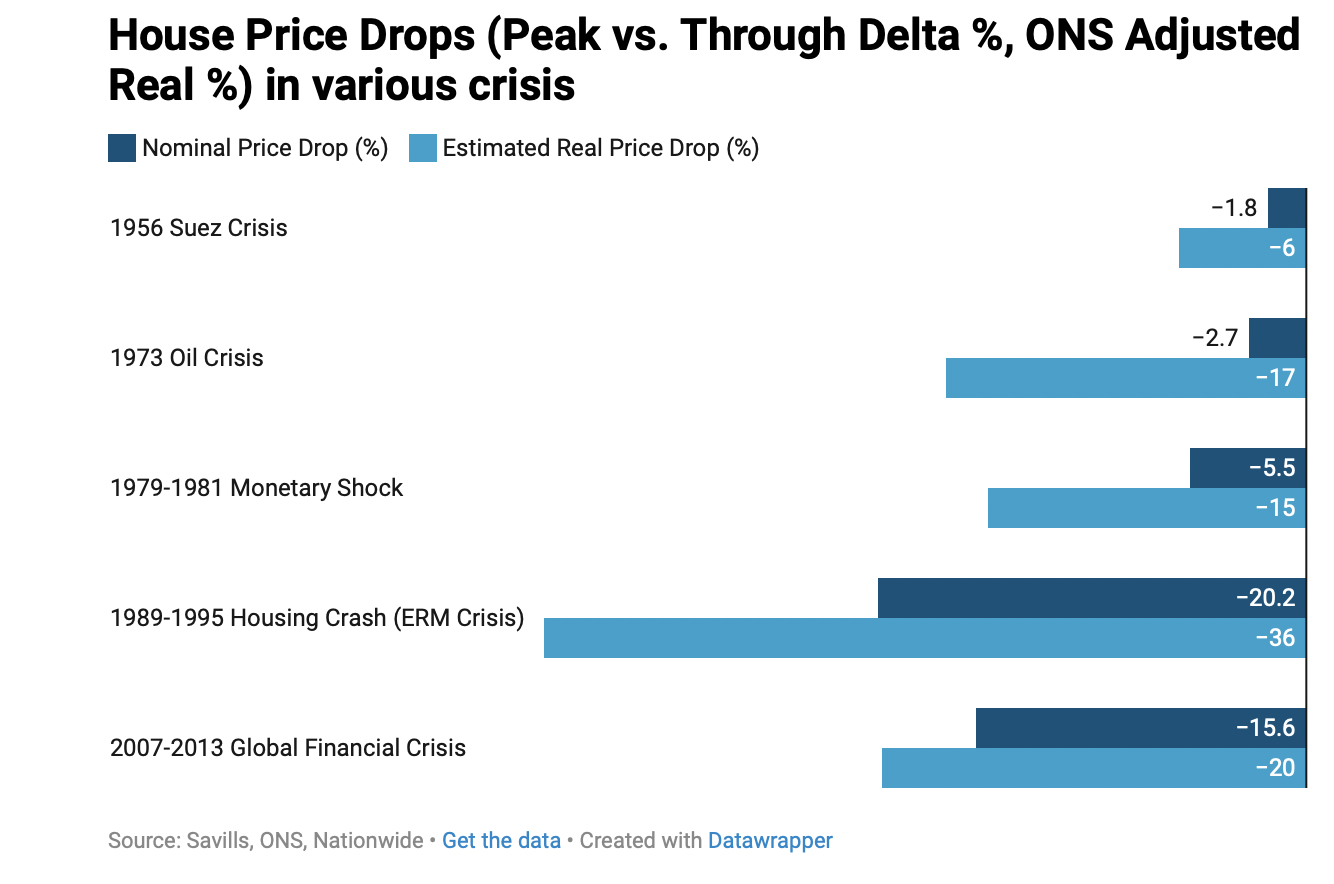

The scale of the rentier bubble was most apparent in the housing market, where the GFC exposed a major asset bubble in the housing market. As we can show below, the scale of hits to the housing market in the post-Thatcher era are much more pronounced than that of pre-Thathcher crisis, showing this increased volatility as a result of asset hyperinflation.

The Policy Response to the GFC

With the GFC exposing the structural over reliance of the UK economy on a few classes of assets that could implode at any point, predictably, the BoE responded by reigniting inflation of assets by initiating one of the most generous expansions of the monetary supply in history. To make one thing clear, I am in no way arguing that the BoE should not have engaged in an expansionary monetary strategy after the 2008 crisis. To argue so would to be in denial of basic heterodox economics7.

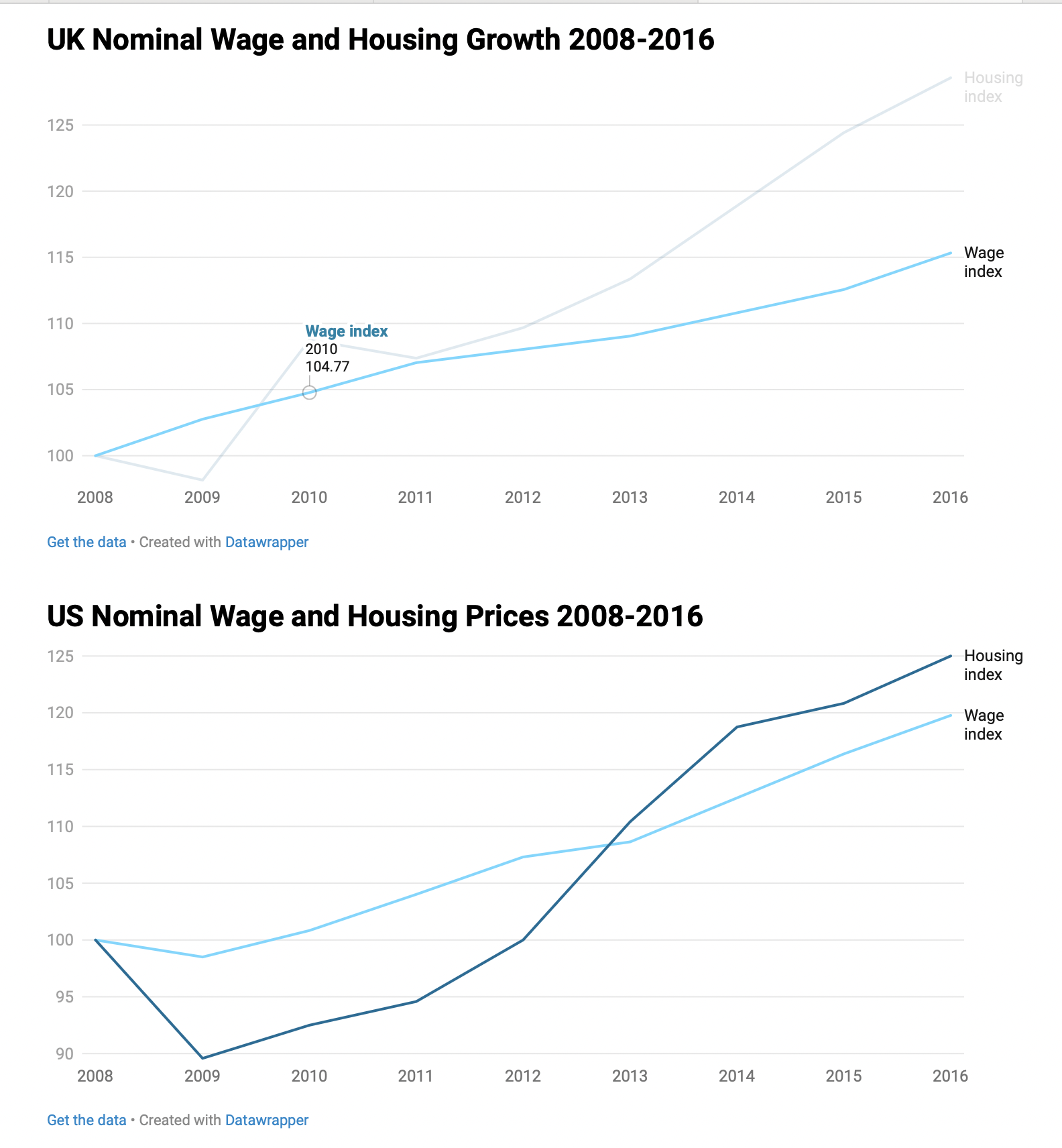

What I am arguing however is that the policy, combined with the Coalition government’s austerity policy, further accelerated the widening between asset wealth and the wealth of the productivity sectors of the economy. We can demonstrate this between a comparison between asset and wage growth in the US and UK.

Both countries had a rapid bounce back in the price of assets (in this case exemplified by house prices). A large part of this can be put down to monetary policy discussed earlier. Reducing interest rates makes storing money in banks a less attractive investment. Quantitative easing reduces the yields of bonds (both corporate and government), and hence makes them less attractive investments. Investors will then move their money to the housing market, resulting in an appreciation of asset prices - about 25% in the US, 30% in the UK.

The primary issue is with wage growth. The US experienced stronger wage growth than the UK (by about 5%) - this can be pinned to the fiscal responses of each country. The US leveraged the low bond yields to initiate generous fiscal stimulus (see the 2009 ARRA) while the UK’s newly elected Conservative government did the complete opposite, tightening the fiscal spending of the economy when investment was badly needed. The result was a slower rate of wage growth in the UK than the US. This bifurcation of recovery, visible in both economic data and political discourse, deepened the rentier structure of the British economy, setting the stage for the stagnation of the 2010s, and to a degree, the 2020s.

The Symptoms of Rentierism: Literature Review

Productivity

As the newly created liquidity following the Carney put flowed into rentier assets (as a result of the UK’s structural dependence on them), instead of into low capital formation into other sectors of the economy. An analysis by the Bennett Institute at Cambridge in 2023 analysed long term trends into capital formation of specific areas of the economy. A pattern emerges, that being the UK struggles in investment into productive sectors of the economy, but remains middle of the pack with investment into rentier assets.

An undercapitalisation of sectors manufacturing, R&D, and infrastructure has resulted in a deprecation of labour productivity within those sectors. Worse R&D investment and infrastructure investment also tends to have a knock on effect upon the rest of the economy. Undercapitalisation is also exacerbated due to firms preferring to financially engineer (stock buybacks, dividends) instead of reinvesting to expand their productive capacity.

Ever increasing housing costs stifle geographical mobility of Labour. A paper by the BMC Public Health Journal finds that increasing house prices can be find to have a relationship with health outcomes - “with lower-income individuals and renters [experiencing] negative health consequences from rising housing prices. This may have resulted from increased stress and financial strain among these groups.” This could have potentially contributed to the increasing levels of health-related benefit claims that are negatively contributing to the UK’s productivity 8.

Underinvestment and Stagnation

The IPPR’s 2017 report Time for Change: A New Vision for the British Economy argued that British has struggled partially because of a business culture that favours short-term returns over investment. Later IPPR analysis found that Britain has an investment shortfall to the tune of £562 billion from 2006. Rentier-driven business goals of maximising asset returns means that reinvestment to grow business is less attractive; the result is a lower level of private investment.

The financialisation of assets can also have a negative impact on growth. An IMF working paper, Too Much Finance, found that economic output is negatively impacted when domestic credit to the private sector exceeds 100% of GDP. According to 2022 World Bank figures, the UK is currently at 130%.

A different IMF working paper, Asset Bubbles: Re-thinking Policy for the Age of Asset Management, also found that asset price inflation can lead to higher costs for land and other capital inputs. This can increase the cost of investment into productive areas (e.g. how land inflation has rapidly skyrocketed the price of HS2) and hence crowd out investment.

Inequality

For those with a more left-leaning slant, there is also academic literature to link the rise of rentier assets and wealth inequality. A piece in the academic journal Economics Bulletin titled Rentier premium and wealth inequality introduces the concept of a rentier premium, which refers to how the wealthy benefit disproportionately on higher returns on rentier assets than that of productive capital.

In the Journal of Economic Behaviour & Organisation, a paper titled Inequality and finance in a rent economy finds that financialisation (in the paper referred to as securitisation, in practice similar concepts) has created a positive feedback loop - with finance sector growth worsening wealth inequality, and worsening wealth inequality driving growth of the financial sector.

Unwinding the Rentier Economy

Reforming Taxation

Taxation reform is a topic I seem to end up writing about in almost every entry of this newsletter. It is one I return to, not out of laziness, but instead necessity. For the purposes of this essay, I will mainly be focusing on how to shift the burden of taxation back onto assets, rather than productive labour.

Wealth taxes are one of the more commonly suggested reforms to the tax system. In concept they sound intriguing, but unfortunately their empirical record leads to a lot be desired. Their tendency to cause capital flight and as result damage levels of investment must be noted, especially in a country like Britain where the economy already suffers from an undercapitalisation problem. The Tax Foundation Europe finds that escalating tax burdens through progressive income taxation and wealth taxes have resulted in effective marginal tax rates of over 100% in Spain, meaning that productive sectors in theory can be put in a situation where earning lower salaries is in their interest. The taxes have a net negative impact on the economy, in almost all sectors. Here’s what the TFE finds in the previously mentioned study:

“Wealth taxes disincentivize entrepreneurship, leading to less innovation and less long-term growth. A wealth tax reduces wages, destroys jobs, and reduces the stock of capital. All income groups are worse off under a wealth tax due to decreased economic activity.”

Speaking of things I talk about too much in this newsletter, a Land Value Tax is perhaps the asset tax that has gained the most prominence in recent years (other than wealth taxes). Land taxes would tax the value of the land under dwellings. A proposal that may be more politically practical than a complete turnover of tax administration would be to replace business rates with LVTs. An article by the NEF made the case for this change. Business rates harm productive enterprise, and an LVT should shift the burden onto productive assets. I have discussed the case for an LVT before (although I may update it). The LVT can be designed in a way to acheive a variety of different economic goals. Take a piece by the Oxford Institute for New Economic Thinking that discusses a ‘green’ LVT, that would allow for deductions of LVT based on the energy efficiency of property.

Another reform that could be made is to capital cost recovery policy. Capital cost recovery refers to the ability for firms to write off investment against tax. The UK has a relatively ‘stingy’ attitude to these deductions relative to other OECD countries, which the UK’s relative rate of business investment. One could imagine additional funds raised by an LVT or other tax going to incentivise investment through increasing capital cost recovery policy. The TFE finds that extending capital cost recovery to full expensing of construction and other investment categories could have a positive impact of 2.5% on long run GDP.

Liberalising the Planning System

The 1947 Towns and Country Planning Act, as argued earlier, was one of the first pieces of legislation that put Britain on the road to rentierism. Reforming the legislation to return to a middle ground between the unchecked greenbelt construction of the 30s and the current strangulation of the private sector should be an aim. One of the more comprehensive breakdowns and criticisms of UK planning law, Policy Exchange’s Rethinking the Planning System for the 21st Century, suggests altering the system away from being a discretionary system towards a rules based mixed-use zoning model.

Current discretionary systems guided by the vague language of the ‘public interest’ incite institutional inertia, where planners within the UK often are tasked not with actually addressing the macro impacts of the housing crisis but instead with trying to predict market preferences to be in line with said ‘public interest’. The Policy Exchange in Balancing the Books argues that the UK is the only country in the entire G7 that does not have a zoning system 9 and as a result depresses the amount of housing and commercial spaces; with inefficiencies having a negative impact on investment and as a result, a negative multiplier on growth.

The planning process for NSIPs (Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects) remains inefficient, despite some steps forward made by Labour’s recent Planning Bill. This especially slows the process of new energy projects, such as with the case of Hinkley Point C. On the topic of the green transition, the Centre for Climate Engagement at the University of Cambridge finds that slow planning systems are also slowing the development of micro-scale developments like home solar panel installations. New planning systems could encourage green developments through perhaps mandating solar panels for new developments.

Head of Policy at Britain Remade, Sam Dumitriu also makes the case that reforming planning policy, especially relaxing policy regarding urban containment, could allow for far greater levels of investment into productive ventures like green tech and data centres.

Miscellaneous Policy

This essay has mostly focused of rentierism of assets in the classes of land, infrastructure, and finance. Brett Christophers, however, in his book, Rentier Capitalism explores more forms of potential economic rents.

Christophers alleges that overly long IP protections have transformed IP into a rent asset. Licensing fees and legal threats create high barriers for entry, enforcing market behaviours similar to that of oligopoly. These high barriers to entry hence disproportionately harm small businesses.

Potential policy fixes could involve narrowing the scope and duration of IP protections, or having a ‘use it or lose it’ clause for more forms of IP - it is currently used for trademarks, but others have suggested extending it to patents and copyrights. Placing restrictions on ‘evergreening’ - the practice of filing minor variations of IP to extend personal exclusivity - would have to be reformed.

Some also criticise how publicly funded research is licensed - with the IP gained from publicly funded research often being privatised. Alternative policy direction could be pushing research that creates open source hardware or the creation of a national IP domain. Expanding R&D contracts with state retention by the state has been argued by Mariano Mazzucato in The Entrepreneurial State to be a key reason for the United States’ earlier technological advancements.

A form of taxation that has gained prevalence recently due address the often self serving nature of financial institutions is a financial transactions tax. The Tax Foundation finds that the policy can be effective at lowering financial asset prices, but also comes with the risk of decreasing overall GDP and confidence in the economy - that being due to the role financial sectors still play in propagating productive sectors of the economy. Other policy, like regulation of stock buybacks, may prove to be more prudent and less harmful onto the wider economy.

Germany is a country from which the UK can learn from, with the OECD finding that the rent-to-income proportion in the UK being 35.2%, higher than the German proportion of 23.3%. There are several policies that cause this.

Germany has a ‘codetermination’ system, which allows worker to elect members to the board to represent their interests. Regional banks play an important role in promoting Mittelstand (SMEs). Public banks play an important role in local economic development. Collective bargaining is based on sectoral bargaining rather than being firm by firm. Industrial policy is similarly focused on regional development, with a ‘tweener’ R&D system focused at encouraging public and private sector cooperation - for example, the Fraunhofer Institute. The UK could try to learn from this policy.

Conclusion

This essay has shown how the UK economy became increasingly centred around rentier systems - through land and real estate, with policy like the 1947 TCPA, or even financial system - with the economy becoming increasingly centred around banking systems, shown by the magnitude of the damage done to the economy during the 2008 financial crisis.

These have had devastating consequences upon the economy. Part of this is due to the negative impacts on productivity that the rentier systems have. Rentier systems stifle innovation and negatively impact levels of investment in the economy; which has several negative knock on effects on the economy, contributing to low growth and lower levels of tax revenue.

Rentier systems have become embedded in the UK economy. But with smart policy design, it is not important to unwind the policies. Reforming taxation, shifting the incidence of taxation to rentier assets from productive labour can help to shift the incentives on the economy. Reforming the planning system will also have a large impact, allowing for an expansion of supply in rentier assets of infrastructure and land. More creative policy directions, like reforming IP laws to reduce hoarding of IP can also stifle the prevalence of rent seeking.

Thank you for reading, for what has been my longest post up to this point. I hope you have enjoyed! I promise the next posts I will try to talk about things other than the planning system and land value taxation. See this post as a culmination of that interest within my newsletter.

This section regarding the British history of Housebuilding is based off Samuel Watling’s article for Work In Progress, ‘Why Britain Doesn’t Build’. Absolutely worth a read.

2 In contemporary economics, land has traditionally considered to be completely inelastic with respect to supply. Despite this assertion a study by the Joint Research Centre found much more variability in elasticities, with coefficients ranging from 0.08 to 4.65. Hence it is not unreasonable to say that the reforms of the TCPA had a distortive effect on the supply of land, with landowners gaining more power to constrict supply. While the quantity of land remained fixed, the willingness to supply was decreased with respect to price as a result of increased landowner rights.

3 The ‘big bang’ refers to an explosion in the UK financial markets after the Thatcher government and the London Stock exchange settled a sweeping antitrust case made by the Office of Fair Trading. Ensuing changes in the rules of the London Stock Exchange allowed London to cement its place as one of the financial capitals of the world. Further reading can be seen in a series of collected retrospective essays from the CfPS.

4 Wage data was compiled using AWE data from the ONS/BoE - “three centuries of economic data” - then calculated using the ONS inflation tool. Data for house prices was compiled from the Bank of International Settlements’ long run housing data. Additional housing data was compiled from Watling & Breach 2023 from the Centre for Cities, based on Holmans, 2005. Data for equities were less straightforward considering the FTSE was not established until 1984. The data used was an OECD official indicator for the UK, that being the FT 30 Proxy - available via the OECD.

5 Historical data for wages were obtained from the BoE/ONS centennial data set. Modern data for salary was from the ONS. The Nationwide House Price Index was used for the housing part of the dataset. It is important to note that the FTSE was not established until 1984, so the proxy for the 1980 was taken FT30 data. Continuing data for the FTSE here. All inflation estimates were taken using the RPI (due to the prevalence of housing as a consumption good within the dataset) within the BoE RPI tool.

6 It is difficult to establish a definitive casual relationship between tax changes and vacancy rates due to the lack of continuous and comprehensive long term data on vacancies. Some isolated datasets exist like the 1973 London Housing Survey and 1981 Department of Environment Housing Statistics Dataset, however these are often non continuous and are only collecting data from a specific region. National series on vacancy rates like the ONS’ Dwelling Stock by Tenure and Vacancy tend to predate the removal of schedule A in 1963. As established by Levin in Taxation of Land and Property, 1977, p. 98, tax owners often had an incentive to either utilise property to pay the tax. Kemp in Vacant Property and the Housing Crisis, 2004 says that the removal of the tax lowered the opportunity cost of asset hoarding and hence removed incentives for proper utilisation of land.

7 It is that attitude to policymaking is why I find similar criticisms of rentierism by authors like Brett Christophers very unhelpful. Rentierism is a concept that is commonly used in heterodox economics, but also Marxist economics. I aim to criticise the rise in rent-seeking from a liberal perspective. Perhaps the most influential economist ever - certainly one of the most famous Liberal ones - Adam Smith - advocated for the taxation of rents on land and property. The concept of productive labour’s opposition to rent-seekers very quickly lends itself to a comparison to the Marxist theory of ‘a surplus value theory of labour’. As a result, many Marxist-adjacent economists will sometimes use rentierism as their economics-equivalent ‘theory of everything’, an exercise equally unhelpful as the Marxist overreliance on surplus value theory. One could argue that these theories’ blend of physics envy philosophical science and often-vague and populist-tinged tirades against capital/rent-seekers makes them closer to Marxism than most self-proclaimed communist movements in the modern world.

8 There seems to be a breaking point in 2020 for these ‘diagnoses’. Perhaps attribute this to just Coronavirus, but I believe there are cultural factors responsible that go beyond just that. Mental illness has become something of a ‘fad’ recently (I can’t believe I’m actually typing that, but I’m not joking), especially as a retreat for those increasingly socially isolated (this goes back to lockdowns, but also the internet age as a whole). Please read some of Freddie DeBoer’s work on this topic.

9 Zoning systems are not perfect and are not a perfect one size fits all solution to the UK’s planning woes. The US has a very strict zoning system which has essentially mandated suburban hellscapes on the whole country. If the UK was to ever implement mixed-use development, I would prefer a system more similar to that of Japan.