Investigating the UK's productivity crisis

Now that the storm of coronavirus and inflation seem to be calming, the flatline in UK productivity looks to be the issue that captures the attention of the UK economic community. However, the productivity crisis is an issue that has really been around for a lot longer than the ‘new’ issue it is sometimes treated as.

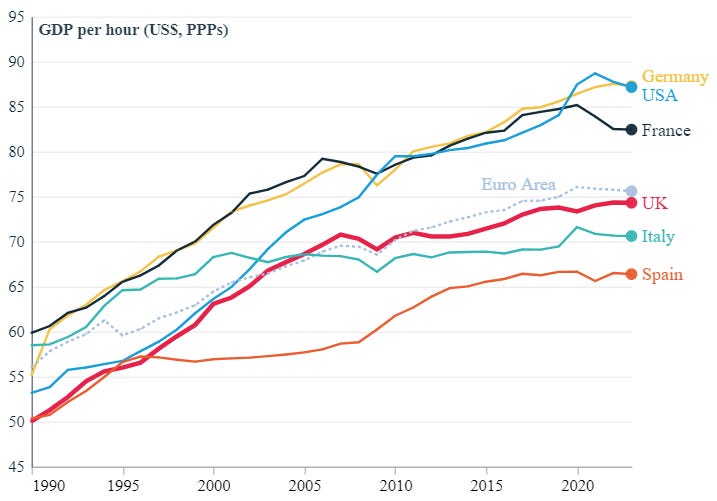

UK productivity growth against comparable developed countries (Credit: The Productivity Institute)

UK Productivity growth has been stunted since the 2008 financial crisis when you consider the value of GDP per hour worked. Average growth in this measure from 2010 to 2022 was 0.5%.

The consequences of this lack of growth is stark, and, thankfully, has been acknowledged by most sides of the political spectrum. Consider the right wing Telegraph, “Britain is facing its greatest slowdown in productivity in decades”, and the left wing Guardian, “The slowdown in Britain’s productivity growth over the last decade is the worst since the start of the Industrial Revolution 250 years ago”, broadly being in agreement with the diagnosis of productivity issues.

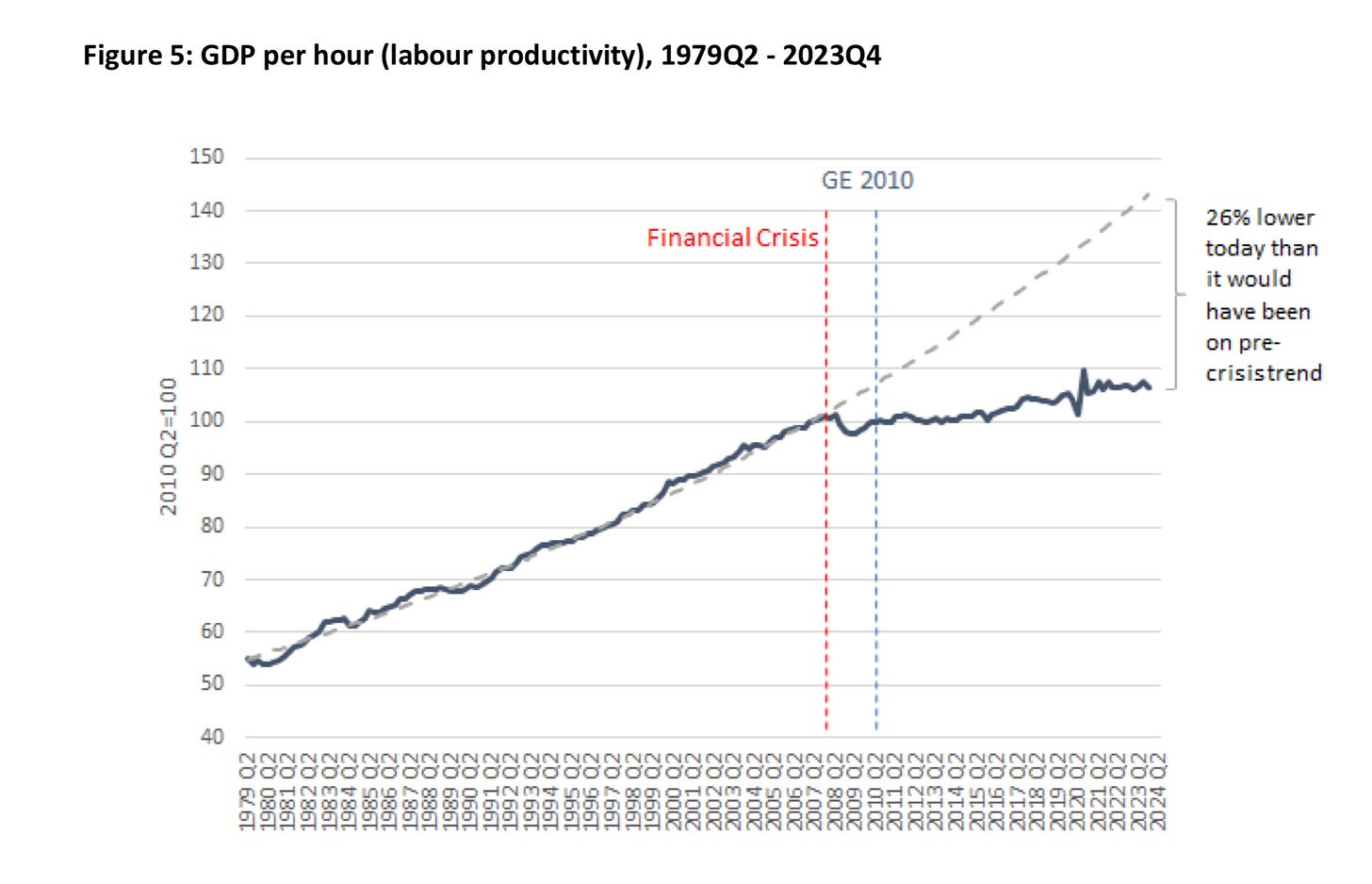

Considering the symptoms of such a crisis is also important. According to the IFS, GDP per capita is £11,000 lower to what would be expected with pre-decline trends. Real wages have been depressed since the financial crisis in part to productivity stagnation, decreasing by 2.4% due to inflation. According to the CEP, the slowdown in growth in part due to productivity has caused a £60 billion tax shortfall per annum.

Labour productivity relative projected pre-crisis growth (Source: CEP)

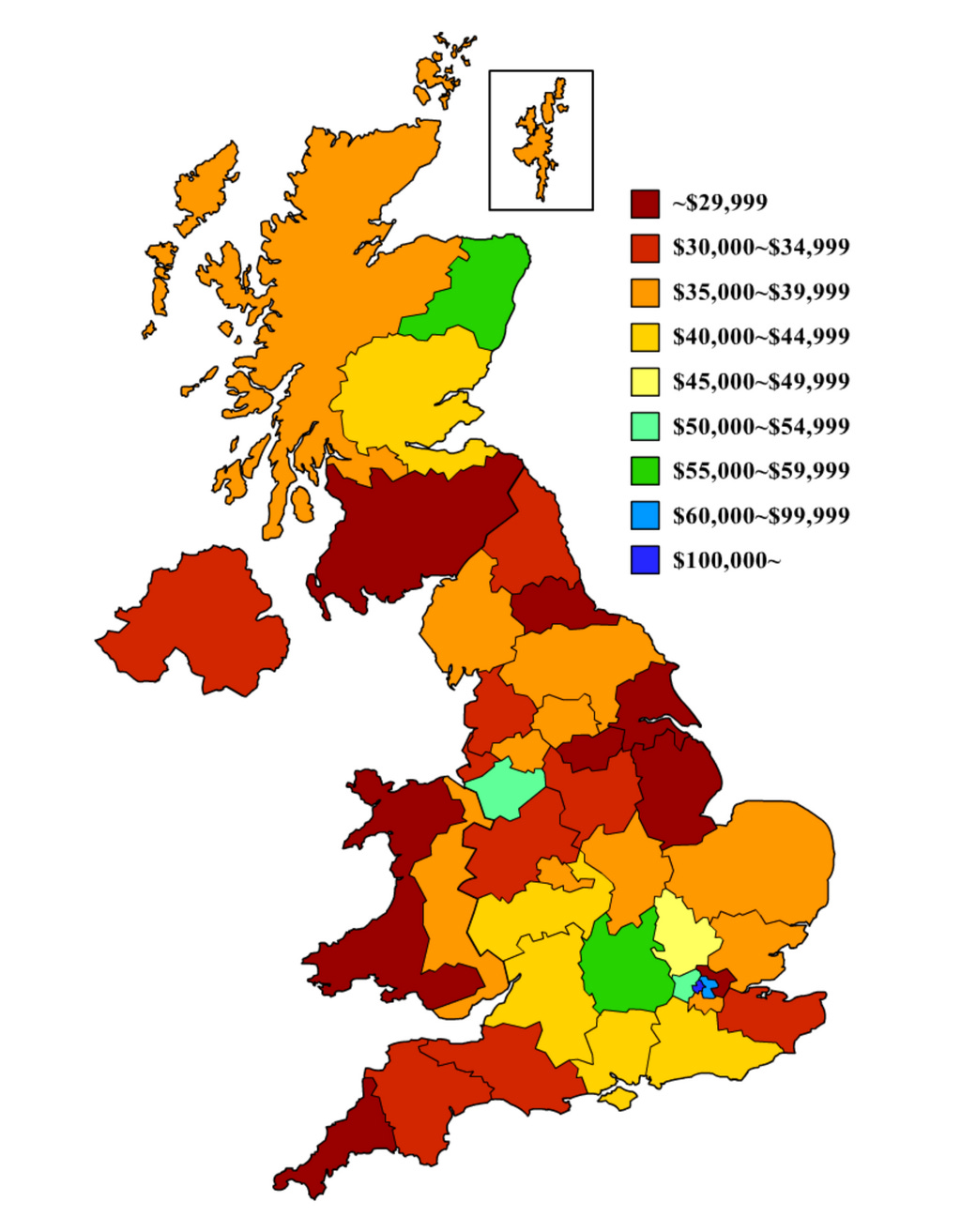

There is a large productivity gap regionally. Take for example the southeast and northeast. In part due to inequality in venture capital funding (68% in UK, 4% in northeast), and infrastructure funding(£1,200 in London, £400 in Yorkshire), the UK ranks amongst the worst in the OECDS’s spatial inequality, with output in London exceeding Wales and the northeast by 40%.

The UK’s regional income inequality (Source: NagNandoor, data compiled from ONS)

This regional inequality then contributes to the regional inequality of income. This contributes to the IFS finding the geographical wealth divide in the UK getting worse.

Finding the root causes of the UK’s productivity crisis is therefore crucial to then understanding any potential policy fixes. The Productivity Institute outlines three key causes for this: underinvestment, inadequate diffusion and an absence of joined-up policy-making.

Levels of investment in the economy have dropped since the start of the 21st century, with investment also being distributed unequally across regions. Lack of investment into human capital has lead to the demand for training to drop creating a vicious circle, where the drop in demand causes a further fall in supply. Underinvestment has been ingrained into the UK economic system.

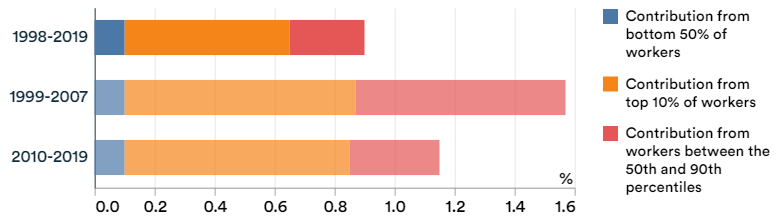

Productivity growth of workers grouped by current productivity, non financial business economy (Source: Productivity Institute)

Data also suggests that the slowdown in productivity growth is primarily coming from the lack of growth from workers in the 50th to 90th percentiles of productivity. Firms that employ these decently-productive employees have the potential to be more productive, but failures to utilise technologies from top-level sectors and Britain’s stagnant trade and lack of FDI have hampered potential growth.

The UK also suffers from heavily overcentralised institutions. Tools to increase productivity like education and transport are almost exclusively managed by Westminster. The tools that councils do have, like control over planning, is restricted through the perverse incentive of appeasing NIMBYs.

The IEA (predictably) mentions overregulation and over taxation, especially on the financial services sector as another problem. Some may roll their eyes at this claim. There is definitely something behind this claim however.

https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/GCX3O/1/

The UK has middle of the road tax rates for corporation tax, high rates of income tax, and one of the highest rates of VAT amongst the developed world ¹. This is not even considering the payroll tax for businesses, that was recently increased in the budget. Altogether, the UK has a tax problem, but not one on the same level as nations like France or Germany. Comparing the overall tax burdens of nations with their average growth over the previous decade shows a weak correlation of lower taxes leading to overall higher GDP.

https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/8HkyC/1/

In fact, I would argue that it is not necessarily how much tax is levied in the UK, but instead how we levy tax. The doctrine of taxation the UK has followed since the Beveridge era has been one focusing primarily on maximising the progressiveness of the taxation system (i.e. low taxes for the poor, high for the wealthy). If the UK wanted to alter its taxation model to encourage productivity, then I think moving towards a Georgist model of taxation could be intriguing.

In Progress and Poverty, American economist Henry George argues for a model that shifts away from the model of punishing productive behaviour that dominated progressive political discussion in the late 19th century. Think about the things that are taxed most often in the economy:

Income taxes, which punishes our Labour that contributes to the economy

Corporation taxes, which punishes the enterprise that contributes the economy

Payroll taxes, which punishes employers paying their workers for their Labour, which again, contributes to the economy

Sales taxes, which punishes consumption that (mostly) positively contributes to the economy

George argues for taxing the exploitation in the economy. Taxing the ownership of land was one of his key tenants, as the ownership and hoarding of land assets does not contribute positively to the economy. Contemporary Georgists also argue for a carbon tax, and other Pigouvian taxes on activities that do not contribute positively to the economy - like sugar, alcohol, and cigarettes. By taxing unproductive assets like land and carbon, Georgist principles could redirect investment toward innovation and labor, addressing the UK’s underinvestment trap. I have already written an entire article on Land Value taxation in the UK, but considering its more focused impact on productivity should be considered.

If reducing the total tax burden is also something desirable, then reducing the size of the public sector should be a priority.

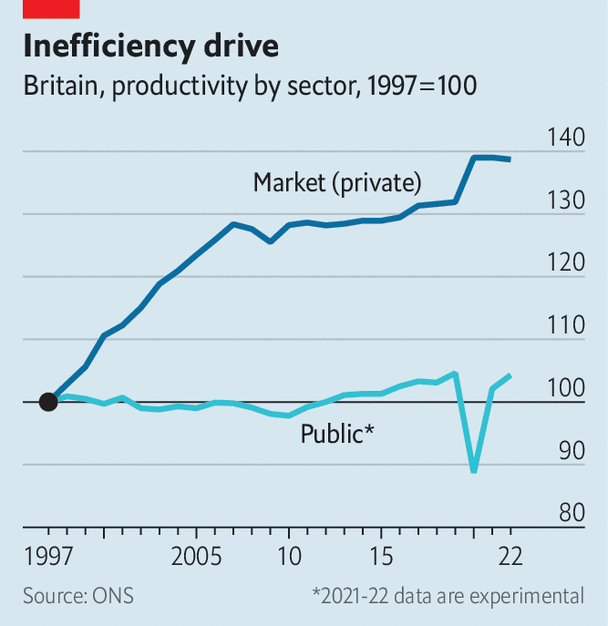

Change in productivity of public sector vs private sector from 1997 (Source: The Economist)

The public sector has struggled in increasing its productivity, especially since the coronavirus. Trying to cut the public sector should be considered when trying to fund tax cuts - perhaps in a more measured manner than Musk though.

The NHS is one of the driving causes of the public productivity problem - so maybe Labour’s NHS reforms can help in the area of public sector productivity.

When it comes to the IEA’s regulation point, I do largely agree with their points. The UK nanny state has gotten extremely out of hand (case in point: the Football Regulator). All I can say is however: good luck convincing the public. The only silent majority in the UK is the one that wants to ban everything, and then ban everything harder.

Returning to the Productivity Institutes’s listed causes of productivity, there are several policy directions that could be taken. I have written an article already on the issues with local governmental organisation, but going further, giving English councils the right to handle education and transport (and adequately funding them) would go wonders to allow for actual investment strategies to emerge in the UK.

Fixing the investment shortfall is not easy. Many factors impacting investment are effectively purely sentiment-driven within an economy, which creates a cycle where underinvestment reduces sentiment, further harming investment. The best way the UK could encourage investment in my opinion is to relax its planning rules, but similarly to deregulation of business, that is not exactly a popular opinion.

There is a potential factor over the horizon that may be able to help the UK’s productivity: artificial intelligence. Thankfully, AI taking over seems to be something even the NIMBYs Luddites of UK society seem unable to stop, and it has similar productivity boosting potential to that of the internet. AI is still in its primitive stages, which is perhaps the most encouraging thing regarding the technology.

I am of the belief that the real AI revolution will come once specialised AI models start becoming more commonplace. General use AI is helpful, but models that are trained on datasets focused on a single exact purpose - for example, an AI trained only on a nation’s medical records and history of medical research (as scary as it may sound), that can then take over some of the low-importance GP appointments, will be the real boon for productivity. This then ties into the point of the slowdown in growth from semi-productive firms, as AI is exactly the type of innovation that the Productivity Institute suggests as a fix for semi productive firms. Bringing AI promise back to the UK should be a priority, something that proposed expansions of Oxford and Cambridge should help with.

To conclude, the UK needs a policy vision looking forward to fix the productivity crisis. There are options heading forward, like tax reform and local governmental reorganisation. AI also seems to be emerging as another option to improve UK productivity. However, flip flopping on policy and ignoring the issues cannot be options, as has been the standard in the UK over the previous decade.

¹ This data does not count the state sales taxes or income taxes that are prevalent in the US and Canada.