Will the Last Person to Leave Britain Please Turn out the Lights

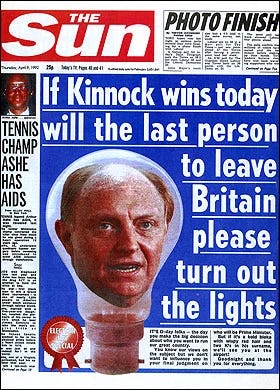

The Sun’s endorsement of John Major prior to the 1992 election was seen as being highly influential, and preceded perhaps the far more iconic headline, “It’s the Sun Wot Won It”

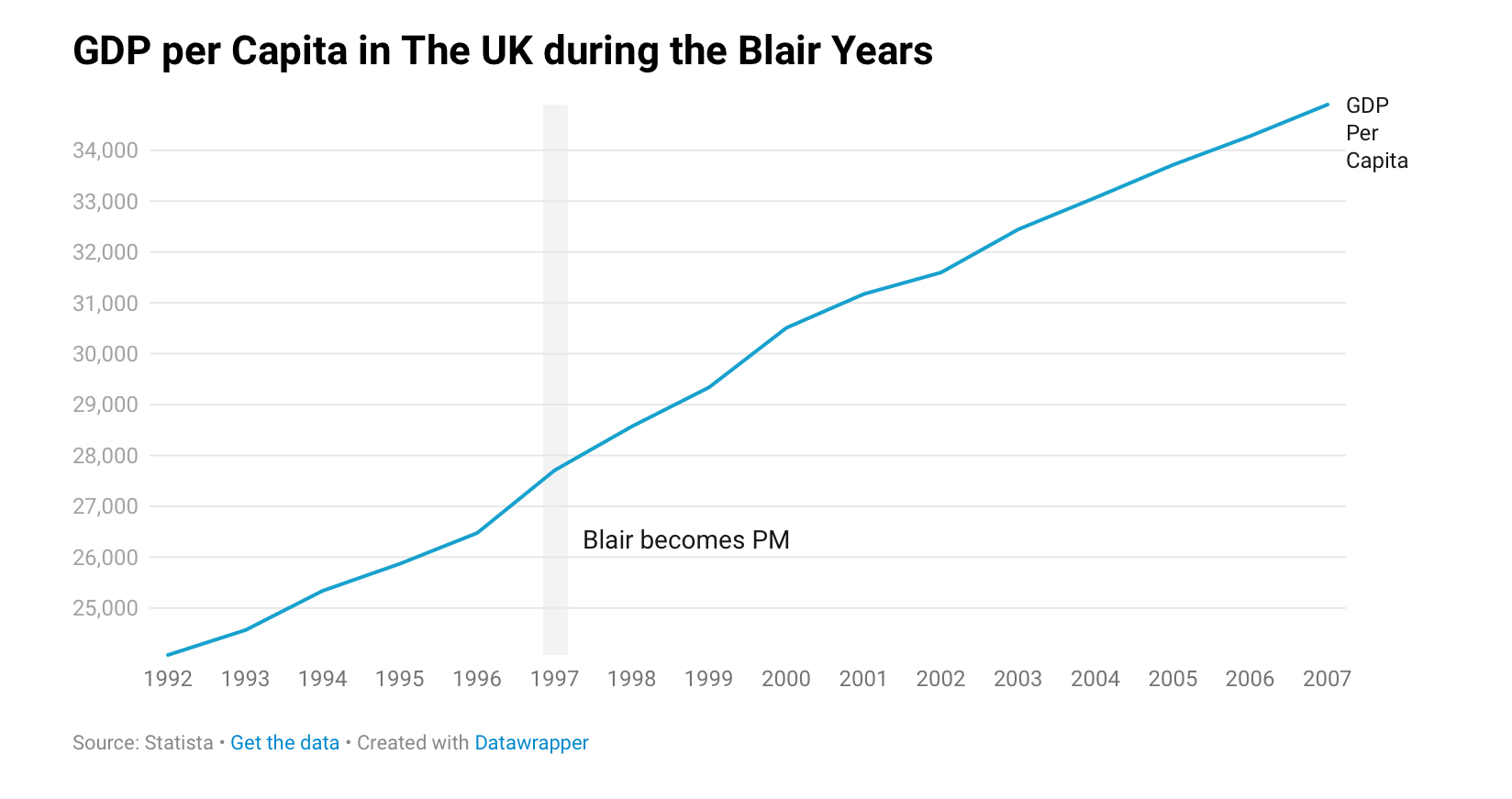

In 1992, in ever-so-expected Murdoch media fashion, the Sun ran a piece fearing that a Labour victory would plunge Britain into darkness. Labour would take power (although not in 1992, instead 5 years later under the command of Tony Blair), and Britain would not be plunged into darkness. Instead, Britain would… pretty much continue its trends as it had prior to Labour’s takeover.

Crisis averted. The Sun’s vision of Britain destruction after Labour’s takeover was thankfully, proved false ¹. The late 1990s were a time of unprecedented global stability, at least relative to the fears of nuclear war that preceded it. The 90s and especially the early 2000s were not a perfect time to be alive, but if looking at it from the brain of a Homo Economicus, it is apparent that it was a fairly prosperous time. After the end of Blair’s term in 2007, the UK was one of the wealthiest nations in the world. The UK was the 8th wealthiest country in the world when measuring by GDP per capita according to the IMF ².

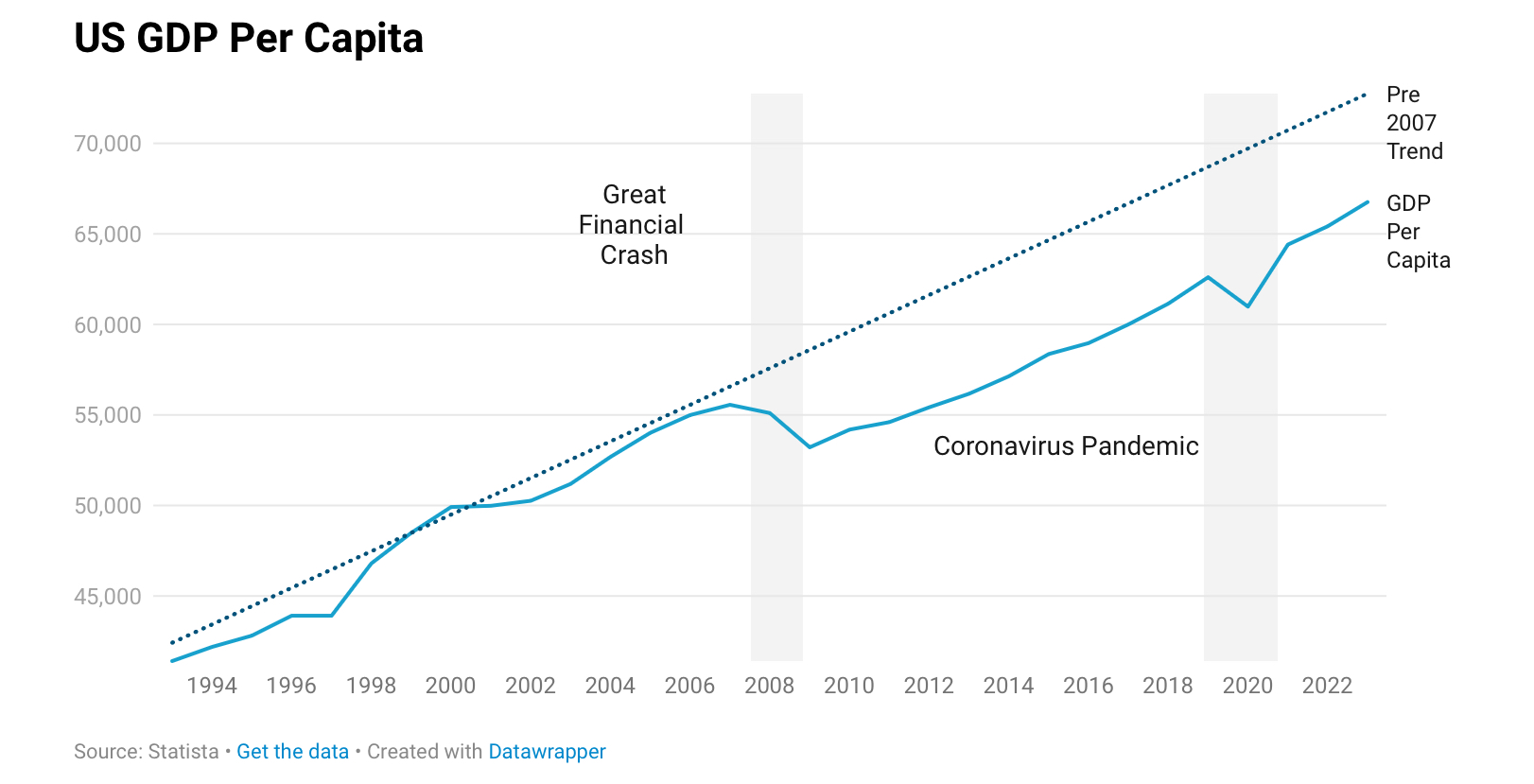

If you were to tell an economic forecaster in 2007 that the world would have to endure a world wide pandemic and a great financial crisis, they would revise their growth estimates down when trying to estimate the GDP of the UK in 2025. The United States, one of the most dynamic economies in the world, is an example of this, with growth falling (only slightly) under the pre 2007 trend.

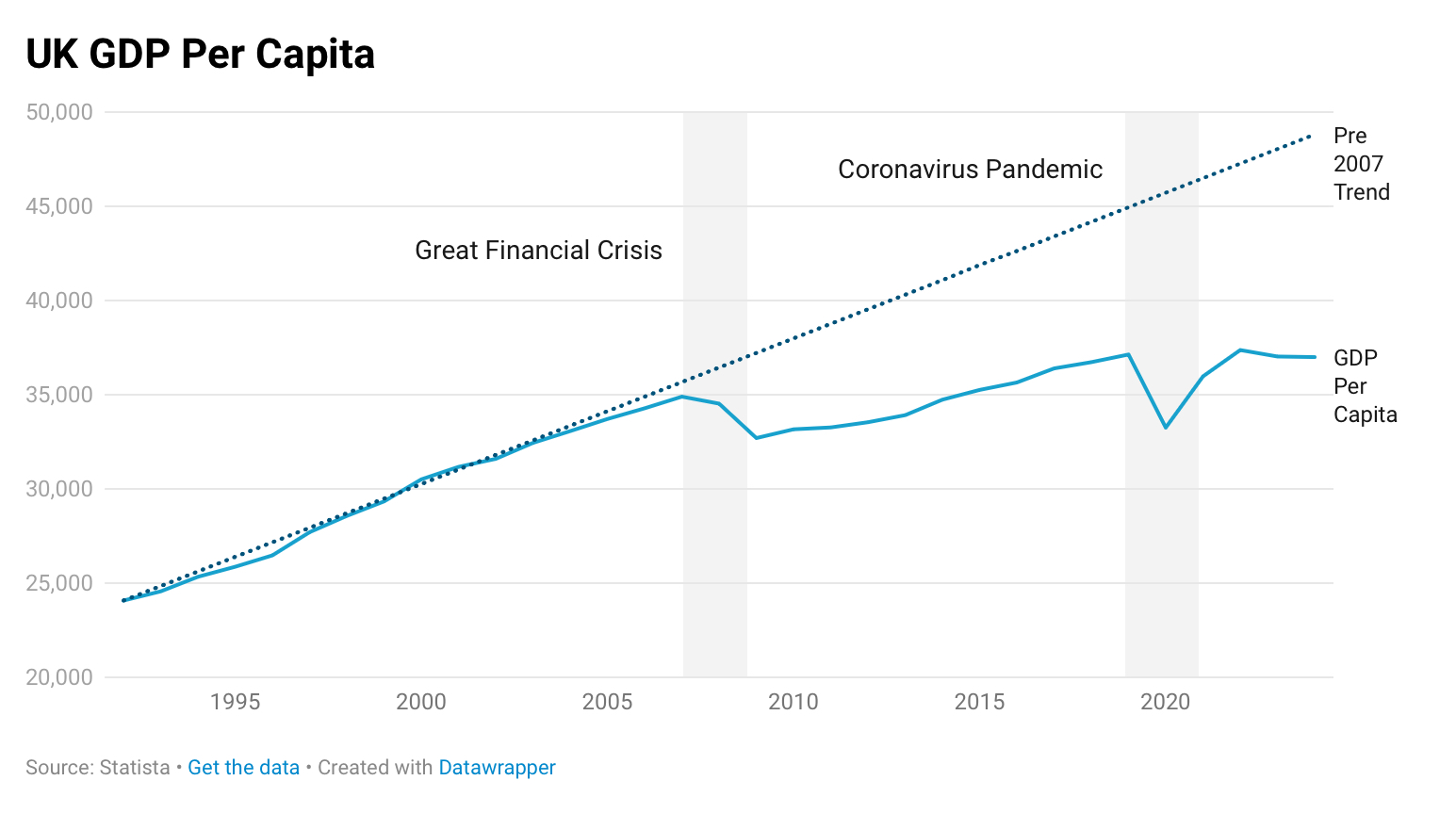

Still, this trend looks miraculous when compared to the UK. This is where it gets grim.

That growth from the financial crisis onwards is concerning for the UK. No longer are we one of the top-10 wealthiest countries in the world, but now find ourselves in the 30s, behind the likes of Slovenia and Brunei. Sentiment around the UK economy is genuinely depressing. Take for example, the first 3 results when you search ‘UK economy’ into YouTube.

It gets sad pretty fast. The fact that this lack of growth has now persisted under SEVEN Prime Ministers, all of whom have tried and failed to try and fix this broken economy, is even more discouraging. It’s easy to feel hopeless, as often it feels like nothing works. Austerity? Didn’t work. Protectionism? Made things worse. Insanely expansionary demand-side policy? Sort of ³ worked, but now all the progress on reducing the deficit during austerity has been wiped out, and the geniuses at the BoE are still quantitatively tightening, fighting an output gap issue that doesn’t exist. £223 billion in unfunded tax cuts? Our PM got outlasted by a lettuce. Whatever Starmer and Reeves are trying? Jury’s still out, but it’s not exactly looking good.

The only winner of this economy…

It seems like the Sun’s nightmare of a Britain plunged into darkness may come true after all.

I could whine about how terrible things have been with the economy in the UK, but that is mostly a useless exercise. Instead, we should look to how to at least make some progress into fixing the economy. Understanding what has caused Britain’s stagnation is firstly important to understand how it can be fixed.

Productivity stagnation is probably the most obvious cause of the stagnation, considering that it can serve as a pretty solid explanation for the post 2010 below average growth. I have already written an article on this topic, but to summarise, the causes of this issue largely lie with a lack of investment (will be covering this later), a bloated civil service and regulatory state, and inoptimal methods of taxation.

Austerity is another debated cause of this stagnation. Being able to fully debate and understand the impact the Austerity had on the UK is an incredibly complex task, and one that, apologies, is likely too long for this article.

I can point you to a discussion between Joeri Schasfoort and Dr. Jo Michell into this topic, who covers the economic backing behind austerity in a far more detailed manner that I possibly could.

My view on austerity is that it was not necessarily the cause of Britain’s economic woes, but instead made our recovery a lot more difficult than it ought to have been. It did not dig the hole per se, but just kicked away the ladder. One could imagine that getting ourselves out of our productivity deficit could have been far easier if we had our workers of the future going through an education system that has not repeatedly faced budget cuts ⁴. Austerity’s reduction of the deficit also did little to restore business confidence in the UK; and if it had, then it would be quickly erased by the next factor to be discussed.

Brexit’s biggest impact was on exchange rates, where sterling lost large amounts of its value immediately after the referendum. While this makes exports more expensive, it meant that import prices increased substantially, which especially hurt the UK’s import reliant businesses. The impact of the referendum on enterprise can be seen on how business investment flatlined immediately afterwards.

(The dip in investment immediately after the UK leaves the EU is misleading, as it coincided with the Coronavirus pandemic).

Brexit did not necessarily cause Britain’s problems, but did contribute to the failure to recover from them. UK leadership has absolutely failed to take advantage of any opportunity that Brexit might have provided. There has not been a major trade deal with the US or Australia since Brexit, and it has left British businesses struggling, and handicapped the level of growth the UK has experienced. Cambridge Econometrics finds that, by 2035, the UK will have:

3 million fewer jobs 32% less investment 5% less exports than if it remained in the EU. Even arch-brexiteer Nigel Farage thinks Brexit has failed up to this point.

Our Coronavirus response was not necessarily problematic. Schemes like Furlough, while not exactly great for the long term economic outlook, were likely necessary to prevent short term collapse. I am more critical of the BoE’s post-Coronavirus monetary strategy however. Perhaps the most easiest policy fix for the UK is ending compensation for the BoE’s losses, which has cost taxpayers billions especially since the BoE began its QT program. While I see the justification for the initial tightening, considering the economy was surpassing 10% annual inflation at some points, this program has gone on too far, increasing bond yields in a time where many aspects of the economy are in desperate need of government investment.

Any policy reform that can bring greater levels of investment into the economy should be the number one priority. Increasing the capital stock can allow output caps to relax and the BoE to return to expansionary monetary policy. Increasing investment however is a policy objective that has been tried by almost every government, with most not achieving substantial progress. ‘Increasing investment’ now just feels like yet another government buzzword if anything.

However, there are some concrete measures that can bring investment back into the economy. My preferred choice is addressing planning regulations, allowing greater labour mobility, reducing fees for businesses by lowering rents, and not to mention its pronatalist effects ⁵. If possible at all, establishing trade deals with either the US or Europe should be another priority, which could also have a positive impact on animal spirits within the economy.

Reforming taxation is another, one that I have written about previously. Reforming how we treat University applications is another; I am of the opinion that subjects that are shown to have greater positive externalities (engineering, medicine), should be free at University level, with less societally beneficial degrees (sorry arts students) remaining at the same £9250 annual cost. Incentivising these economically beneficial degrees can reduce unemployment, and hopefully encourage more firms to base themselves in the UK. Others may rightfully point out however that drawing the line between what is beneficial and what isn’t can quickly become subjective and hence problematic.

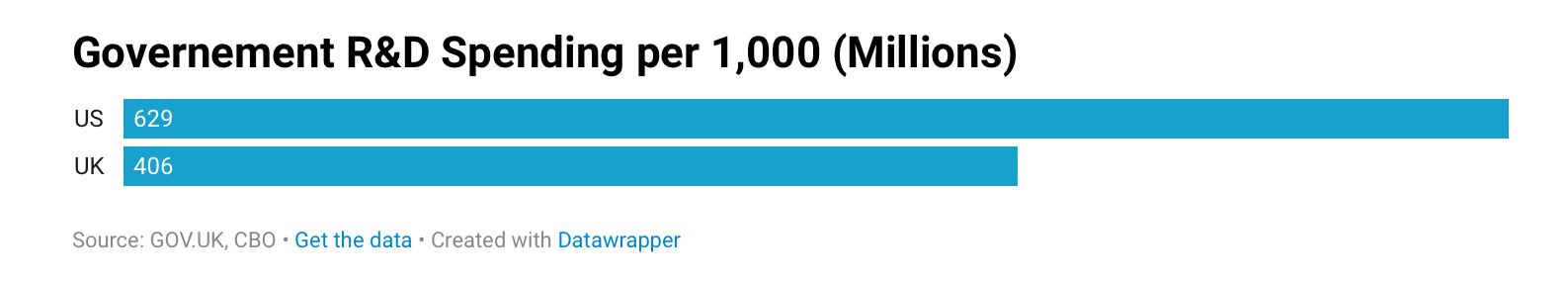

Increasing R&D subsidies and reducing rates of corporation tax can encourage corporations to relocate to the UK. The United States might not be a big spender, but have correctly identified the economic benefit of R&D subsidies.

So therefore, while the current outlook of the British economy may not exactly be encouraging, is it not a hole that we can get ourselves out of. If we are able to overcome our cultural opposition to success of any kind, then there are a number of options on the table. It isn’t easy - but it isn’t impossible.

You can keep the lights on for now.

¹ The Sun actually proved themselves wrong. During the 1997 election, the Sun switched their endorsement from the Conservatives to Labour.

² This is excluding oil states like Qatar, and micro nations like the Cayman Islands. Measures like median salary may be preferable, but I struggled to find data from 2007 on that statistic.

³ The Carney Bailey put was not quite as aggressive as the Powell put tried by our transatlantic allies, but the nature of the UK’s financial institutions meant that we got stuck in a liquidity trap pretty fast. The impact of the furlough scheme is still up for the debate.

⁴ Retroactively reverting austerity cuts will do little as well. Sadly, the damage has already been done to the economy.

⁵ The policy is pronatalist in the sense that it allows families easier access to positive environments to raise children, hence encouraging child birth.